AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GOTTINGEN

(1936-1938)

When we had made our travel arrangements, we knew that we were scheduled to arrive in Europe a full month before school started. Our course of action was deliberate: we wished to acclimatize ourselves before settling down, and the opportunity to do so had been provided by my German friend Wilhelm Vauth. He had invited us to spend a month at his parental home in the farming community of Rusbend, near the town of Bckeburg, in the beautiful Weser Valley of Schaumburg-Lippe, and to it we directed our steps. First, however, we had to pass through the Rotterdam customs offices, to set our feet on Dutch soil, and to survey a portion of the Lowlands where our parents first saw the light of day.

Our coming ashore at Rotterdam was made pleasant by the reception we received. Greeting us at dockside were distant relatives of Hilda who had earlier been apprised of our coming. Oom Hannes and Tante Grietje, as we called them, along with their adult daughter Adriana, welcomed us to The Netherlands, conducted us to their modest home, and prepared for us an ample supper. For want of space, however, they were unable to put us up for the night. Thus, after spending a pleasant evening in conversation, we rented a room in a nearby Salvation Army hostel where, amid primitive conditions, we slept the sleep of the innocent. The night’s lodging cost us $1.15.

Adriana and her boyfriend, Henry Roelofs, called on us early the next morning and took us on a full day’s tour of the city and its busy harbor. Oom Hannes and Tante Grietje were no less hospitable: in order to provide us with sleeping accommodations that night, they, despite our protests, vacated their bedroom and slept in the bunk-lined cabin of their tugboat, which was moored nearby. Living in the house at the time was Tante Grietje’s aged mother, a sister of Hilda’s paternal grandmother. She was keenly alert, and it was a delight to hear her speak in Dutch of things long past. Her sleeping quarters, we noticed, consisted of a space built into a wall, and this intrigued us.

On the following day, the first of October, we headed by train for Amsterdam, stopping en route for a look at The Hague. We slept that night in an Amsterdam hotel and spent nearly the whole of the next day in an exploration of the city and its prestigious Ryksmuseum. At 6:00 p.m. that evening we entrained for Appeldoorn, where we were met by Hilda’s uncle, Harry Veldsma, who put us up that night in his comfortable home.

On the next day, the third of October, we took a train to the border town of Bentheim, where, after passing through customs, we transferred to a German train bound for Bckeburg. Wilhelm met us upon our arrival there, and after we dined on sauerkraut and bratwurst at a local Gasthaus, he drove us in a borrowed car to his home in Rusbend.

* * * * * *

The house we entered was set on a “farm” of ten or fifteen acres on which, between stints of outside employment, Vater Vauth raised corn and garden produce. One came up to the house from an unpaved road and entered it after traversing a patio fitted for outdoor relaxation. I do not remember how the inside rooms were arranged, but I know that there was a large kitchen, a larger dining and sitting room where we ate and socialized, and a parlor furnished with, among other things, a foot-pumped organ that Hilda sometimes played. We reached our upstairs sleeping quarters by ascending a steep staircase, and the bed we occupied was spread with a thick feather quilt. What to us was unusual about the house was the fact that the barn, which stabled two cows and several pigs, was attached to the house and was in a sense one with it. It was at the far end of the barn that the two-seater non-flushable toilet stood, and the journey to it led past the penned animals, who by their grunting and mooing gave Hilda some uncomfortable moments, especially when the journey had to be made at night by the light of a lantern.

Living in the house besides Vater and Mutter Vauth, who appeared to be in their early or middle fifties, was a twentyish daughter named Enna, a teen-ager named Sophie, and two much younger children, whose names matched our own, which is why during the month of October and (we were told) for a considerable time thereafter they were known to the world as “Kleine Heine” and “Kleine Hilda.” Wilhelm also lived at home, but he was undergoing instruction preparatory to ordination and this involved his periodic absence from the scene.

Living in the house besides Vater and Mutter Vauth, who appeared to be in their early or middle fifties, was a twentyish daughter named Enna, a teen-ager named Sophie, and two much younger children, whose names matched our own, which is why during the month of October and (we were told) for a considerable time thereafter they were known to the world as “Kleine Heine” and “Kleine Hilda.” Wilhelm also lived at home, but he was undergoing instruction preparatory to ordination and this involved his periodic absence from the scene.

Hilda knew no German, so her first days with the Vauths were quite difficult; but she soon learned to communicate reasonably well, and this stood her in good stead when we arrived in Gottingen. She and I were generally at leisure and had time for our own pursuits, but Hilda assisted with the house work and I helped Vater Vauth harvest the corn and do the daily chores. Kleine Heine was in the process of mastering the intricacies of German script, and since I was setting myself to the same task, the two of us could often be found at the table absorbed in our joint endeavor.

I was not helpful in easing Hilda’s transition to life on a German farm. On the very evening that we arrived in Rusbend, Wilhelm proposed that he and I attend a Hitler rally that was to be held the next day in a field near Hameln, a town famed for its fabled Rattennger. Unmindful of the fact that this would leave Hilda amid virtual strangerswhose language she did not understand, I readily, even eagerly, agreed to the proposal. We set out on bikes the following morning and arrived at the distant scene in time to hear Hitler address a vast crowd of awed and admiring citizens. It was here that I first heard the “Heil Hitler” chant and saw arms outstretched in the Nazi salute, and the performance had a chilling effect on me. When the rally ended, we set out for home; but before we had gone very far, I, being unused to riding a bike, grew faint from exhaustion. Wilhelm escorted me to a nearby inn where, upon retiring, I fell into a deep sleep that lasted all night. Wilhelm meanwhile continued on his way home and informed a distraught Hilda of my indisposition and unintended absence. After receiving directions from the proprietor of the Gasthaus in Krckeberg, I found my way back to Rusbend on the following day, and was greeted by Hilda with what may fairly be described as mixed emotions.

Early on we had placed an ad in the Gottingen Tageblad inquiring about apartments for rent and, when we had received a number of replies, Wilhelm and I set out for Gottingen. On October 14 we boarded a train at Kirchhorsten and proceeded via Hannover to Hildesheim, where, after touring that picturesque town, we spent the night. The next morning in Gottingen we engaged furnished rooms at No. 4 Obere Masch Strasse, and arranged to have our trunks shipped from Rotterdam to this address. As soon as our work was completed, we left Gottingen and, via the train and our bikes, returned to Rusbend toward noon on the sixteenth.

Early on we had placed an ad in the Gottingen Tageblad inquiring about apartments for rent and, when we had received a number of replies, Wilhelm and I set out for Gottingen. On October 14 we boarded a train at Kirchhorsten and proceeded via Hannover to Hildesheim, where, after touring that picturesque town, we spent the night. The next morning in Gottingen we engaged furnished rooms at No. 4 Obere Masch Strasse, and arranged to have our trunks shipped from Rotterdam to this address. As soon as our work was completed, we left Gottingen and, via the train and our bikes, returned to Rusbend toward noon on the sixteenth.

Hilda, meanwhile, was not confined to the house. The two of us sometimes sat in privacy on the bank of the canal that flowed past the house; we took walks along the road, stopping sometimes at the nearby inn for a stein of beer; and we made joint trips to Bckeburg, Vehlen, and Stadthagen. It was during this time, too, that Hilda accompanied Enna on a trip to Porta Westfalica.

We were nonpaying guests at the Vauths during our four-week stay in Rusbend, and we deeply appreciated the family’s Christian kindness and hospitality. We sought to express our appreciation by providing occasional treats, and before our departure for Gottingen we placed in each family member’s hand a gift representing our gratitude.

We bade farewell to the Vauths on October 31 and boarded a train for Hannover. We surveyed the city that day and lodged there that night. On the evening of the next day, November 1, 1936, we took up residence in our newly acquired, two-room, mid-town apartment.

Before we settled down for an academic year of work, we took notice of the fact that a black American by the name of Jesse Owens had embarrassed Hitler by winning three gold medals in the Berlin Olympic games in August. We also learned, this time to our own embarrassment, that the American Ezra Pound was broadcasting for Mussolini and that his fellow countryman, Fred Kaltenbach, was doing the same for Hitler. It was not long before we also heard that Franklin Roosevelt had handily defeated Alf Landon in the race for the Presidency of the United States.

* * * * * *

Frau Klempt was our landlady at the Obere Masch address, and we paid her fifty-five Marks (about $13.50) a month for the two rooms we occupied in her second-floor residence. The medium-sized bedroom was furnished with twin beds, a loose-standing wardrobe, and a small chest of drawers on which stood the porcelain wash basin and water pitcher with which we performed our daily ablutions. A door at the corner of this room led onto a balcony, which we seldom used but from which we could survey the whole of the short block on which we lived. The living room-study area contained a desk set at a window, a bookcase, a small settee, a round table with chairs, and a coal-burning stove. The single door that led into our rooms opened on a hall; on the other side of it was the toilet room as well as the living quarters of Frau Klempt and her two teen-aged children, Ilsa and Herbert. The Klempt kitchen stove was placed at our disposal; but after a trial period, Hilda found it expedient to exercise her independence and prepare meals in our own apartment. To this end we bought a Spiritus Apparat, a small kerosene stove with one burner on which food could be heated when patience and caution were exercised. Of course, we had to buy the kerosene, coal, and kindling wood we used, and to pay the electric bill and radio assessment; but since we had no phone, telecommunications cost us nothing. We had no icebox or refrigerator either, and this required us to shop daily for groceries. Early on, Hilda assumed the shopping duties, and her German vocabulary in the food category soon outstripped my own. She was able to buy everything we needed, except that the baker would sell her only day-old bread and then but half a loaf, and that Herr Schlimpen would allow her to buy only two eggs at a time, preferably such as had a crack in them. The house we lived in was one of a solid block of lawnless houses that ranged along the cobblestoned street and abutted the narrow sidewalk.

It was just a few blocks from the railroad station, and just off the tree-lined Goethe Allee by which one could easily reach the commercial establishments on Weenderstrasse as well as the beer Keller in the ancient Rathaus.Gottingen was not a large town: its population did not exceed perhaps thirty or forty thousand; but it was an old town with many reminders of its medieval origin. Located in the province of Hannover, it lay in a valley surrounded by forested hills, one of which, the Nikolausberg, lay within walking distance and attracted many hikers, including ourselves. Just when the site was settled is not certain, but it is said that the deepest foundation underlying the Albanikirche dates from the days of Charlemagne. What is known is that the city’s Rathaus dates from the fourteenth century and that the once fortified and still standing wall that outlines the inner city, was in place before the Rathaus was built. The wide wall, now severed in spots by crossing thoroughfares, was shaded by lofty trees and much used by strollers when we were there. Hilda and I often walked it on Sunday afternoons. Still gracing it is the small stone house that Bismarck built and lived in when he was a student at the university.

It was just a few blocks from the railroad station, and just off the tree-lined Goethe Allee by which one could easily reach the commercial establishments on Weenderstrasse as well as the beer Keller in the ancient Rathaus.Gottingen was not a large town: its population did not exceed perhaps thirty or forty thousand; but it was an old town with many reminders of its medieval origin. Located in the province of Hannover, it lay in a valley surrounded by forested hills, one of which, the Nikolausberg, lay within walking distance and attracted many hikers, including ourselves. Just when the site was settled is not certain, but it is said that the deepest foundation underlying the Albanikirche dates from the days of Charlemagne. What is known is that the city’s Rathaus dates from the fourteenth century and that the once fortified and still standing wall that outlines the inner city, was in place before the Rathaus was built. The wide wall, now severed in spots by crossing thoroughfares, was shaded by lofty trees and much used by strollers when we were there. Hilda and I often walked it on Sunday afternoons. Still gracing it is the small stone house that Bismarck built and lived in when he was a student at the university.

Dominating the skyline were the city’s churches: visible for miles were the twin towers of the Johanniskirche and the lofty spire of the Jakobikirche. These churches and the less imposing Mariankirche were unheated in winter, and on cold days the worshipers, we among them, sat huddled in overcoats and gloves during the entire service. The town was famous for the ancient Gasthaus on Kurzenstrasse called the “Schwarzen Bren” and also the sculptured fountain known as the “Gnselieselbrunnen,” which stood on the Rathaus square. On market days the square was full of vendors offering tempting fruits, vegetables, and flowers to the householders who each week were attracted to the place.

The university was clearly the most prominent and influential institution in the city, but its true name was not widely known outside officialdom. Just as the town derived its fame from the university, so the university tended to derive its identity from the town: thus it came to be known to the public as Gottingen’s university or the University of Gottingen. But this was not its real name. Founded in 1737 by the prime minister of provincial Hannover, Gerlach Adolph Von Mnchhausen, the school was by its charter called the Georgia Augusta University, and that name it still retains, although hardly anyone now thinks of calling it that. The university had an auspicious beginning, and, though comparatively young as European seats of learning go, it has had a memorable career.

It drew its earliest students from the ranks of German nobles and landed gentry, and its distinguished faculty has throughout the years attracted students from around the globe. I am unqualified to judge its stature during my residence there, and I suspect that, like other German schools, it suffered under the restrictions imposed by the Nazis and the purges effected by Hitler; but I have no cause to question the competence of my teachers or to complain of their attitudes and behavior. In 1936 the university’s buildings were spread across town, though there was a campus of sorts where a number of the constituent schools and colleges were clustered. Instruction in mathematics and the natural sciences perhaps took on a different form, but in theology and philosophy, and in the humanities as a whole, instruction proceeded by the lecture method. Except in seminars and tutorials, where discussion and dialogue could take place, the typical student could fairly be described as a “hearer” who sat respectfully in an auditorium and listened without comment or rejoinder to the reading of a manuscript by the professor, who in all likelihood would reconstitute it as a chapter in his next book. That mode of instruction and learning had its disadvantages, but it could also lead the student to pursue his own inquiries, and this quite often happened. In my own case, the lectures I heard served largely as stimuli that moved me to read around the subject on which the professor was discoursing.

* * * * * *

When I was enrolled as a graduate student in theology on November 7, 1936, Hilda also entered the university: in the company of a number of her newfound friends she joined a class in “German for foreign students.” The instruction she received not only improved her hold on the language but also introduced her to significant aspects of Teutonic culture.

I began my studies under three instructors. Committing myself to nine hours of course work, I took a four-hour course in “Dogmatik, I Teil” (on the foundations of dogmatics) with Prof. Otto Weber; a two-hour course in the “Grundzge der Theologie Calvins” (on the principles of Calvin’s theology) with the same Prof. Weber; a two-hour course in “Leidensgeschichte” (on the passion of Christ) with Prof. Joachim Jeremias; and a one-hour course in “das Historische Bewusstsein” (on historical consciousness) with Prof. Nohl. These were all lecture courses, and at the outset I attended the scheduled lectures with exemplary regularity. However, this was not the custom of my German counterparts, and in due time I learned to moderate my zeal and be selective. I had some difficulty at first in following the lecturers’ rapid discourse, but I soon became sufficiently proficient in German both to understand what was being said and to respond in kind.

I began my studies under three instructors. Committing myself to nine hours of course work, I took a four-hour course in “Dogmatik, I Teil” (on the foundations of dogmatics) with Prof. Otto Weber; a two-hour course in the “Grundzge der Theologie Calvins” (on the principles of Calvin’s theology) with the same Prof. Weber; a two-hour course in “Leidensgeschichte” (on the passion of Christ) with Prof. Joachim Jeremias; and a one-hour course in “das Historische Bewusstsein” (on historical consciousness) with Prof. Nohl. These were all lecture courses, and at the outset I attended the scheduled lectures with exemplary regularity. However, this was not the custom of my German counterparts, and in due time I learned to moderate my zeal and be selective. I had some difficulty at first in following the lecturers’ rapid discourse, but I soon became sufficiently proficient in German both to understand what was being said and to respond in kind.

I decided early on that I should work toward an advanced degree and, receiving Prof. Weber’s consent to be my sponsor and promoter, I proposed that I write a dissertation on “Jonathan Edwards: A Study in Puritan Ethics.” This subject proved acceptable to Dr. Weber, and securing a set of Edwards’ complete works, I began already in January 1937 to read regularly in these volumes and to take relevant notes. Although broken up by a nearly month-long Christmas recess, the first semester extended from the tenth of November to the middle of March, and during that time I addressed myself as best I could to my studies. But, of course, other things were going on in the meantime.

I decided early on that I should work toward an advanced degree and, receiving Prof. Weber’s consent to be my sponsor and promoter, I proposed that I write a dissertation on “Jonathan Edwards: A Study in Puritan Ethics.” This subject proved acceptable to Dr. Weber, and securing a set of Edwards’ complete works, I began already in January 1937 to read regularly in these volumes and to take relevant notes. Although broken up by a nearly month-long Christmas recess, the first semester extended from the tenth of November to the middle of March, and during that time I addressed myself as best I could to my studies. But, of course, other things were going on in the meantime.

The Thanksgiving season was brightened by the appearance in Gottingen of our friend Leroy Vogel, who had come from Heidelberg to spend a week with us. On Thanksgiving Day we dined together in the “Schwartzer Bren” and expressed our gratitude to God for the many blessings we had received. On subsequent days we took Bird up Nikolausberg and showed him the sights not only in Gottingen but also in Hannoverischmnden. Before year’s end, Hilda and I made other brief excursions into the countryside and visited Lippoldsberg, Bodenfelde, and Witzenhausen. Our social life was not extensive, but the English-speaking students at the university formed a kind of loose fraternity, a number of us got together on occasion for lunch or supper, and almost all of us were present at a Christmas party held in the Ratskeller on December 18.

Although we noticed with mounting interest the preparations made by those in Gottingen who would in piety or indifference observe the anniversary of Christ’s birth, we ourselves did not spend Christmas Day on German soil. We spent it in the company of our relatives in Holland. In the village of Uithuizen, the birthplace of my mother, her only living sister, my “Tante Grietje,” still lived with her husband, “Oom Wiebrand” Bultema, and they had invited us to join them and their children during the Christmas recess. We eagerly accepted the invitation, both for the opportunity it gave us to see the very locale where my parents were born and raised and for the pleasure of meeting for the first time a set of close relatives whom we had not known about until recently. An unmarried daughter of Tante Grietje, my cousin Tena, lived in Nieuwschans, where she practiced nursing, and it was she who met us at the railroad station when we arrived at that border town on December 23. Tena greeted us with the hugs and kisses befitting a near kin, conducted us to her home, prepared for us a sumptuous dinner, and put us up for the night. The three of us took a train the next morning to the city of Groningen, and we went on from there to Uithuizen, where we were most affectionately received by Oom and Tante, and in subsequent days treated with extraordinary hospitality. Christmas fell on Friday in 1936, and on that day we worshipped in the old Hervormde Kerk that my mother attended when she was a child. On Saturday (“De tweede Kerstdag”) we went to church in Oudezijl, and on Sunday we attended services in Roodeschool, where Tjaard Van Ellen, the husband of my cousin Coba Bultema, taught school.

Since I had expressed a desire to see my father’s birthplace in Broek in the “Gemeente” Eenrum, Tjaard proposed that we begin our quest for it on Monday morning. We started out on bike in the direction of Usguert, saw the place where my mother was born, stopped at the “Boerderij Klooster” in Usguert, where my mother had worked as a maid, then went on through Warffum and Baflo to Eenrum. Our inquiries at the “Gemeente Huis” yielded no information about the exact location of my father’s birthplace, but we were told that an elderly pair by the name of Stob lived in Hornhuizen. We took to our bikes and went over Wehe, Kloosterburen, Molenrij, and Kruisweg to Hornhuizen, where we were able to call on an eighty-three-year-old, Cornelius Stob, who proved to be a cousin of my father, and who, with his wife seemed delighted to meet a namesake from America. After a short visit with our genial hosts we returned to Uithuizen. We must have ridden 80 kilometers that day and I was completely exhausted, but I was glad to have made the trip and to have passed through the scenes of my parents’ childhood.

Since I had expressed a desire to see my father’s birthplace in Broek in the “Gemeente” Eenrum, Tjaard proposed that we begin our quest for it on Monday morning. We started out on bike in the direction of Usguert, saw the place where my mother was born, stopped at the “Boerderij Klooster” in Usguert, where my mother had worked as a maid, then went on through Warffum and Baflo to Eenrum. Our inquiries at the “Gemeente Huis” yielded no information about the exact location of my father’s birthplace, but we were told that an elderly pair by the name of Stob lived in Hornhuizen. We took to our bikes and went over Wehe, Kloosterburen, Molenrij, and Kruisweg to Hornhuizen, where we were able to call on an eighty-three-year-old, Cornelius Stob, who proved to be a cousin of my father, and who, with his wife seemed delighted to meet a namesake from America. After a short visit with our genial hosts we returned to Uithuizen. We must have ridden 80 kilometers that day and I was completely exhausted, but I was glad to have made the trip and to have passed through the scenes of my parents’ childhood.

On the following days we visited Oldenzijl, Sandeweer, and Oudeschip and spent a night with Tjaard and Coba in Roodeschool. When the time came for us to leave Uithuizen, we bade our hosts a tearful farewell, expressed our deep gratitude, and proceeded to Groningen, where we spent a day with my cousin Jan Bultema and his wife. Jan, a police officer, had the day off, and he conducted us on an informative tour of the city. We spent New Year’s Day with Tena in Nieuwschans and entrained the next morning for Gottingen and home.

Classes at the university soon reconvened, and my studies during the rest of the first semester continued apace, although the presence of Wilhelm Vauth in early January did not enhance my concentration. Wilhelm was spending ten January days in Gottingen for the purpose of completing his examinations, and he was a frequent guest in our house during his whole stay. Soon after his departure, Hilda and I began taking our warm meal in the student “Mensa.” What we usually had for dinner was a bowl of “Linsen Suppe,” sometimes garnished with a piece of wurst. It was also in January that I bought a bike; the purchase took twenty-three Marks ($6.00) out of our treasury.

In early February, Hilda and I hiked to Rosdorf and made a trip to Kassel. It was no doubt a sign of my growing Germanness that in this month I bought a suit with knicker pants at a cost of thirty Marks; the outfit went well with the walking stick that I had earlier bought for seventy Pfenning. On the seventeenth of February we English-speaking students got together for a “Costm Fest” sponsored by the German Austaushdienst, and a week later the group gave a farewell party for Herr Lautenbach, who, in behalf of the German government, had directed our faltering feet during the period of our orientation.

The month of March was memorable in a number of ways. On the eleventh we celebrated our semi-anniversary. On the twenty-third, Wilhelm Vauth was ordained to the gospel ministry and became pastor of the Lutheran church in Vehlen, near Bckeburg. We sent him a copy of Heim’s Vershnung as an ordination gift. In mid-March the first semester ground to a halt, and in the interval between terms I engaged in some sober reflection: I began to have second thoughts about pursuing the theological course of study. I had enjoyed my acquaintance with Jeremias and Weber, and I no doubt profited from their lectures, but I found that what they contributed to my already existing store of theological knowledge was hardly enough to justify my continuing to plow familiar ground. Moreover, the allure of philosophy had fastened upon me. Therefore, I determined to change course, and on March 25, 1937, at the beginning of the second (or summer) semester, I transferred to the school of philosophy and enrolled in several courses there. During this three-month semester (April through June) I took a three-hour course in “Philosophie der Geschichte” (philosophy of history) with Prof. Heyse; a two-hour course in “Philosophie der Gegenwart” (contemporary philosophy) with Prof. Bollnow; and a two-hour course in “Die Geschichte der englischen Philosophie” (history of English philosophy) with Prof. Baumgarten. To avoid too abrupt a break with the school of theology, I also took a four-hour course in ethics with Prof. Friedrich Gogarten, joined Prof. Weber’s two-hour seminar on Reformed thought, and attended Prof. Jeremias’s weekly lecture on Galatians. Hilda meanwhile continued her studies by taking a university course in English literature taught in the German language.

During that semester I continued my independent study of Jonathan Edwards. Knowing that Edwards was a critical student of Locke and an eminent philosopher himself, I believed that a dissertation on his system of thought would be acceptable to the philosophical faculty, and I at once conferred with Prof. Heyse about this. Although he was the head of the department, he was noncommittal on the subject and referred me to his associate, Dr. Baumgarten, who, it turned out, had already been appointed my sponsor in case I chose to pursue a doctorate in philosophy. Baumgarten was undecided and needed time to reflect; but he reminded me that in any case I would need at least another year to complete a dissertation. He suggested that I ask the people in Hartford to renew the fellowship, and he promised to write a letter in support of my request. I followed his good advice, and already on April 9, 1937, I received a favorable reply from Hartford’s Dr. Johnson: “The faculty has voted the reappointment of you as an Exchange Fellow to Germany for the year 1937-38.” I was, of course, elated with the news and was doubly gratified when on June 3 the secretary of the Institute of International Education in New York wrote: “Our Committee on Selection has granted you a renewal of your fellowship.” I was now assured of another year’s stipend and had gotten a new lease on life. But the precise subject of the projected dissertation remained for the moment undetermined; when at the end of June the semester came to a close, the issue was still unresolved and I had no alternative but to spend the summer in pursuit of Edwards.

In April, I visited Bursfelde with Professor Carl Stange, the honorary “Abt” of the ancient monastery there, and Hilda and I attended a picnic hosted by Herr and Frau Stumer. On the first of May we were present at a local fair and we later visited Mariensprings and Heiligenstadt. But the event of the month was our going off in different directions for diversion and relaxation. Sometime in May the exchange students from various German universities were invited to be the guests of the government on a ten-day Rhine and Midland Tour funded by the Carl Schurz Foundation. The invitation, unfortunately, did not extend to student spouses, and I considered not joining the tour until our friend, Hans Kropatchek, a fellow student at the university, invited Hilda to spend the entire period of the “Reise” in the company of himself and his wife at his mother’s home in Ilfeld, deep in the Harz mountains.

When Hilda sacrificially, and with some trepidation, accepted the invitation, I joined the group of travelers with a somewhat troubled conscience. I saw Hilda off for Ilfeld on May 27, and I joined the bus caravan the next day. Hilda’s stay with the Kropatcheks was pleasant enough but quite uneventful, and she was happy to return home when the period of my exile ended. Our group, meanwhile, was taken on a wide-ranging tour that was both pleasant and informative: we visited Mnster, Kassel, the Wartburg, Bamberg, Nuremberg, Dsseldorf, Hameln, Goslar, Kln, and several other places, in each of which we were feted, wined, dined, and domiciled like princes of the realm. On June 7, after ten days of separation, Hilda and I were together again, and for several days thereafter we entertained each other with tales of our adventures.

With the coming of June, the end of the school year and the prospect of a long summer’s recess were on the horizon. We had already determined where we were to spend the summer; only the details needed fixing. Wilhelm Vauth, still a bachelor, lived with his sister Enna in a large country parsonage in Vehlen, and he had proposed that we stay there during the summer and share household expenses. We enthusiastically endorsed the proposal, and on June 12 I set out on bike on the long journey to Vehlen to inspect the premises and to make final arrangements. It chanced that, as I rode, I met up with a gypsy caravan. As I approached the horse-drawn wagons, a female member of the group signaled for me to stop. When I did so, she asked me for a cigarette, which I promptly provided. She thereupon offered to tell my fortune, but I replied that I had neither time nor money for such frivolities and that, in any case, I put no stock in necromancy and divination. She restrained me for a moment, however, and in dulcet tones said simply that “a great change in the circumstances of your life is about to happen.”

Proceeding on my way, I dismissed the pronouncement as an idle tale and gave it no further thought. Because the distance to Vehlen was great, I lodged overnight in a Gasthaus and arrived at Wilhelm’s quite early on the morning of the thirteenth. I discussed with him our mutual plans for the summer, but made no reference to my encounter with the gypsy. I left Vehlen in late afternoon that same day and rode until nightfall. I slept in a Gasthaus that night and arrived home toward evening on the fourteenth. A visibly excited Hilda met me on the stairs. She held in her hand a letter that she urged me to read without delay, and, when I sat down, I read it with unbelief.

The letter was from my brother George, and in it he congratulated me on my appointment to the chair of philosophy at Calvin College. The news was incredible. I had received no word concerning an appointment from any official source, and the likelihood of such a thing coming at this time and under these circumstances had never entered my mind. Yet the startling news proved to be true, and the smoking gypsy stood wondrously vindicated.

A day or so later, a letter dated June 5, 1937, arrived at our house.

It was sent from Fremont, Michigan, and was signed by Rev. L. J. Lamberts, secretary of Calvin’s Board of Trustees. This is what it said:

Dear Mr. Stob:

The Board of Trustees of Calvin College and Seminary has granted you the extension of licensure. This body took further action that may surprise you. It appointed you to the chair that Dr. Wm. H. Jellema vacated two years ago. When giving you this appointment, it decided: (1) To make this appointment for a period of two years; (2) That in case you may see your way clear to accept, to ask you to devote at least one year to the study of philosophy; (3) To accord you the rank of instructor and to set your salary at $2000 per annum, with the understanding that you will begin to receive this salary after you have entered upon your active work.

You will understand, of course, that the Board does not intend to limit your services to a period of two years, but that it is following the time-honored procedure in the matter of appointments. I hope you will send me a favorable reply before long.

Yours very truly,

L. J. Lamberts,

Secretary

The mail that brought Rev. Lambert’s letter also brought letters from President Ralph Stob, Prof. Henry Ryskamp, and Dr. Clarence Bouma. From these informants I learned something about the circumstances surrounding the appointment. After Jellema had left, and Cornelius Van Til had declined the offer to fill his position, the board had appointed Jesse De Boer as a temporary replacement. Now, in May 1937, the board was again in session and took under consideration two nominations the faculty had presented to it: Dr. Cecil De Boer, professor of philosophy at the University of Nebraska, and Mr. Jesse De Boer, the able incumbent of the chair during the two-year vacancy. But wishing to add to the list of nominees a person with philosophical aptitudes and schooling who was also versed in theology, the board placed my name in nomination. After receiving from the faculty’s education policy committee a nihil obstat regarding the addition of my name, the board proceeded to vote. To the surprise of many both inside and outside the academic community, and no doubt to the consternation of some, I received a majority of the votes and was consequently appointed to the chair Prof. Jellema had graced with distinction and renown for fifteen years.

Honored by and grateful for the appointment, I was nevertheless frightened by it. Sensitive to the demands and responsibilities of the task I had been invited to undertake, I was equally aware of my own limitations and deficiencies; and I wondered why at this early stage in my career I had been brought to this Stunde der Entscheidung. Daunted by the challenge I faced, I was initially uncertain what response I should make. Hilda and I naturally discussed the matter by day and night, and we consulted as best we could our friends and relatives. But the final decision was wrought out of our wrestlings with God. A week or so after being apprised of the appointment, I dispatched a letter of acceptance. Although I did this with some trepidation, I was convinced that my action had the Lord’s concurrence.

Thus, with my work at the university still in progress, and with my twenty-ninth birthday still before me, I had committed myself to teaching philosophy in the college from which I had graduated a scant five years before. A heap of correspondence followed. Stob, Ryskamp, and Bouma continued to write, and kind letters arrived from Professors Broene, Vanden Bosch, and Van Andel; but it was with Rev. Lamberts that I was chiefly engaged in the ensuing weeks. It appeared that the executive committee of the board, with Rev. Lamberts as its spokesman, wanted me to work toward a theological degree and only when that was in hand to spend a year in the study of philosophy. I found it hard to understand the proposal and still harder to concur in it. I informed Rev. Lamberts that I had already enrolled in the school of philosophy in March and argued that the interests of all concerned would be best served if I stayed on course and pursued a doctorate in philosophy. I added that in so doing I should also be fulfilling the board’s demand that I “devote at least one year to the study of philosophy.” The committee eventually saw the wisdom of this proposal and acknowledged that in so proceeding I would be meeting all of the board’s technical requirements.

But another issue was constantly being raised in the correspondence. The Professors Vollenhoven and Dooyeweerd of the Free University of Amsterdam were developing what was popularly regarded as a specifically Christian philosophy which in its cosmic sweep embodied the essential elements of Calvinism, and the committee hoped that I would stay in Europe long enough to pursue a course of study under them. Indeed, it earnestly advised and virtually requested me to spend a postdoctoral year at the Free University. This I was reluctant to do. I did not doubt that I could profit from another year of study and reflection; but the arrangements made to facilitate my stay in Amsterdam were hardly to my liking, and I sensed that the proposed venture could adversely affect the many ties that bound Hilda and me together. The financial support the board offered was in the form of a repayable loan and amounted to only five hundred dollars. I knew that Hilda and I could neither live a whole year on so small a sum nor afford to go further into debt. I feared that my stay in Amsterdam would in all probability entail Hilda’s return to the States, and neither of us relished the prospect of a six- or seven-month separation.

On the other hand, I was a new appointee without much leverage, and Hilda joined me in thinking that I could not cavalierly brush aside the wishes of the board. So we at last capitulated. On January 23, 1938, after a half year’s pondering, I wrote a letter to Rev. Lamberts. In it I said, among other things, “I cannot in good conscience leave the advice of the Board unheeded. Let this writing, therefore, serve as a formal acceptance of your plan and as an expression of my intention to study at the Free University next year.” With that the mass of sometimes confusing correspondence came to a temporary end.

It was on May 28, 1937, that I was appointed instructor in philosophy at Calvin College, and on June 21 I accepted the assignment. On the twenty-third we attended a party given by the English-American “Kultur Kreis”; on the twenty-fourth we celebrated my twenty-ninth birthday; and on the twenty-fifth we went to the opera for a performance of Scipio. The school term was now drawing to a close, and a long summer stretched invitingly before us. On June 29 we shipped our belongings to Vehlen, and on the thirtieth we vacated our apartment and severed our connection with Frau Klempt, our not always agreeable landlady. We had no cause to worry about the following year’s lodging, for it had earlier been determined that when classes resumed we would be living with Prof. and Mrs. Stange in their house on Hanssenstrasse.

Hilda had visited the towns and villages that nestled in the countryside outside Gottingen, and she had spent ten days with the Kropatchecks in distant Ilfeld; but, barred from joining the “Carl Schurz Reise,” she had not visited the German Rhineland. So I proposed that, before settling down for the summer, we take a ten-day vacation and explore that scenic region. Leaving Gottingen on the first of July, we visited Kln, Andernach, Coblenz, Bonn, St. Goor, Mainz, Worms, Heidelberg, Speyer, Wrzburg, Meiningen, Eisenach, and Erfurt. The trip, of course, included a boat ride up the Rhine and, quite naturally, a two-day stay in Heidelberg for a pleasant visit with Leroy Vogel. Arriving back in Gottingen on the ninth, we entrained at once for rural Vehlen, where we took up residence in Wilhelm Vauth’s spacious parsonage.

* * * * * *

The country “Pfarrhaus” that we settled in was flanked on one side by a small grove of apple and plum trees, whose fruit we plucked as soon as it ripened. Out back was a vegetable and flower garden that Enna tended, and all around us were small farms with cultivated fields and meadows where cows and horses grazed. The house was set in a pleasant and peaceful environment: the stone and steepled church stood nearby, as did the residence of the hamlet’s only school teacher. Hilda and I occupied two sparsely furnished upstairs rooms in Wilhelm’s house. A bed, a chair, and a stand supporting a washbowl and water pitcher stood in our sleeping quarters; the adjoining room became my “study”: a small table served as my desk, and we fashioned a bookcase out of crates. Hilda purchased fabric and made curtains for the windows. We did not feel deprived; considering the state of our pocketbooks, we felt privileged to be living there.

Hilda assisted Enna with the housework and meal preparation. Wilhelm and I, though engaged in our own work, pitched in where we could. For example, I was frequently dispatched to purchase food and supplies from the only store that served the neighborhood. To this end I rode the trusty bike that I had shipped up from Gottingen.

We spent our days pleasantly in the performance of our varied tasks, and on Sundays we worshiped in the church where Wilhelm preached the gospel with competence and lan. Wilhelm was a member of the “Bekenntniskirche,” which had prepared the Barmen Declaration, and he had no sympathy at all for the “German Christians” who had endorsed Hitler’s anti-Jewish laws and proscriptions. In his public utterances, however, he had to be circumspect and prudent, for the Gestapo had long ears. In addition, Wilhelm’s older brother had been, to the dismay of his parents, for some time a brown-shirted member of the party’s “Schutz Abteilung.” A person of that sort would not hesitate to indict any deviant, even though he be a brother.

My correspondence with the people at Calvin continued during our stay in Vehlen, but soon after our arrival there I addressed myself to serious study. I continued reading in Jonathan Edwards, and by the middle of August I had finished writing two long chapters on Edwards’ ethics. I continued to hope that the philosophical faculty would accept a dissertation on Edwards’ moral philosophy; but, being unsure and desiring certainty, I went to Gottingen in late August to confer with Prof. Baumgarten, my appointed mentor. Baumgarten did not object to my proposal, but he suggested that I might do better by considering more modern thinkers, especially such German philosophers as Dilthey, Jaspers, Heidegger, Rickert, Neurath, and the like, or even Nietzsche. As we continued to talk, I began to be persuaded by his arguments. The discussion then turned to my interest in religion and theology, and he proposed that I consider Max Weber, who had written epoch-making works on the typology and sociology of religion. This appealed to me, for a treatment of Weber would involve me in a study of how an apparently value-free empirical method can be employed to uncover the rationale of valuative behavior.

Before we parted, we had tentatively agreed on a subject: “Die Leitenden Kategorian der Interpretation in Max Weber’s Systematische Religionssoziologie.”

The subject would later be modified, but I returned to Vehlen resolved to suspend my work on Edwards and to fix my mind on contemporary German theories of concept formation. With the coming of September, I read as widely as I could in Nietzche, Misch, and Dilthey, but lacking Weber’s works, I had to postpone a study of the master himself until later.

During our stay at Wilhelm’s we made short trips to Obenkirche, Stadthagen, Minden, and Porta Westfalica, but we could usually be found at home tending to our business. We hosted occasional guests, among them the Priestlys, whom we had met in Hartford, and in late July we entertained my Dutch cousins Tena Bultema and Tjaard Van Ellen for several days. During this time I also received word from Clarence Bouma that he had placed in the July and August editions of Calvin Forum an essay on “Graeco-Roman and Christian Ethics” that I had earlier prepared for his course in senior ethics at the seminary.

What particularly marked our stay in Vehlen was the tragedy of death and the heavy burden of sorrow that we were forced to bear. The blow fell most heavily on Hilda. Late in August or early in September we received word that her sister Therese had on August 22 died in childbirth at the age of thirty-three. “Ted,” as we called her, was Hilda’s favorite sister, and her premature death affected Hilda deeply. The weight of the loss was increased by the fact that distance prevented our attending Ted’s funeral. When the news of her death reached us, her body had already lain for several days in a stone-marked grave.

We were still recoiling from the shock of Therese’s death when word reached us that the seven-month-old son of Mart and Therese had been electrocuted when he touched a frayed lamp cord on the living room floor. This tragic death occurred on September 17, and our hearts went out in sympathy and love to our dear brother and sister. But there was more to come. Just as we were ready to leave Vehlen, we received the news that Hilda’s father had died of a heart attack on September 30. We learned later that he had worked that day as usual but after supper had lain down on the sofa to relieve a faintness he felt. Some minutes later he lay dead. He was but sixty-five years old. Mr. De Graaf was a God-fearing man, an elder in the church, and in all his dealings with people a gracious and considerate gentleman. “Ted” likewise was a child of God and a fitting wife to her husband, Dr. Tom De Vries, professor of chemistry at Purdue University. The knowledge that these two dear ones were now with the Lord did assuage Hilda’s grief, but it could not cancel her bereavement or wholly erase her sorrow. That we were nevertheless able to joyfully celebrate our first wedding anniversary on September 11 was no doubt due to the mitigating power of God’s good grace. We dined that day in Bad Oeyenhausen, and we reviewed the year amazed at all that had occurred in it.

We left Vehlen on October 1, 1937, and, as we had planned, we spent the next two weeks in The Netherlands. We made our home during this period with Hilda’s uncle Harry Veldsma, who lived in Appeldoorn with his wife Grietje. We spent pleasant days with our relatives there, but I varied the routine of everyday life by pedaling my bike as far north as Groningen and Uithuizen. My purpose was to gain further information about my ancestors, and I was able to gather a considerable number of relevant facts at various town halls. I visited Zwolle, Kampen, and Meppel en route, and from Uithuizen I rode to Ulrum, where I mounted the pulpit from which Rev. De Cock launched the “Afscheiding.” Of course, I renewed acquaintance with Oom Wiebrand and Tante Grietje, as well as with Tjaard and Coba, and their hospitality proved to be as gracious as before. Hilda was well entertained in Appeldoorn, and I had ventured forth with her encouragement and blessing. We ended our stay in Holland on the fifteenth of October and were back in Gottingen on the sixteenth and ensconsed in our new quarters at 10 Hanssenstrasse.

* * * * * *

Prof. Stange and his wife occupied the two lower floors of the large mansion-like, turreted stone house in which we now resided. A gate in the six-foot-high steel fence that enclosed the grounds provided access to the house, and an enormous key unlocked the front door. We occupied two large rooms on the third floor. A window in our bedroom afforded a view of the street, and another in our living-study room looked out on a lawn in the rear of the house. Our rent came to fifty Reichsmarks (about $12.50) a month, which included maid service as well as all utilities. We ate breakfast and supper in our rooms but took our noon meal with a nearby caterer who ministered to the appetites of students. I still remember with delight the fresh crisp “Brtchens” that the baker delivered each morning to our door. We were very pleased with our accommodations and happy to be well placed a full two weeks before the school year began.

During the thirteen months we had spent in Europe the world had not stood still, and certain happenings had not escaped our notice. In 1937, Franklin Roosevelt began his second term as President of the United States; Neville Chamberlain succeeded Baldwin as Prime Minister of England; Edward, Duke of Windsor, married Wallis Simpson after the coronation of his brother George VI; Japan attacked China and occupied its coastal regions; Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s seminary at Finkenwalde was disbanded by order of Heinrich Himmler; Martin Niemller was imprisoned by the Nazis, first in Sachsenhausen and later in Dachau; and the formation of the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo axis, which portended no good, shook up the somnolent statesmen of the West.

In The Netherlands, the “Wysbegeerte der Wetsidee” being pro-mulgated by Dooyeweerd and Vollenhoven came under attack with the publication of Prof. Hepp’s Dreigende Deformatie and Rev. Steen’s Philophia Deformata. In that year, too, the Zeppelin Hindenburg was destroyed by fire at the naval airbase in Lakehurst, New Jersey, with the loss of many lives; Amelia Earhart was lost in an attempt to circumnavigate the globe by air; and John D. Rockefeller died at the age of ninety-seven.

* * * * * *

The second school year began in early November 1937, and I addressed myself with vigor to my studies. In the winter semester I enrolled in three two-hour seminars, each of which entailed writing critical papers, and all three of which were taught by Prof. Heyse, dean of the philosophical faculty. One of these was on the “Grundfragen der Philosophie,” another on “Kant’s Prolegomena,” and the third on “Hegel’s Jugendschriften.” In addition, I attended three two-hour lecture courses, one with Prof. Baumgarten on “Englische Philosophie,” another with him on “Hegel’s Philosophie des Geistes,” and a third with Prof. Knig on “Grundfragen der Zeitlehre.” While engaged in these twelve hours of course work, I began to read assiduously in Max Weber and to a degree in William James, because for a time I contemplated writing a dissertation on “Die Wertung der Religion bei Max Weber und William James.” But by the beginning of 1938 I sensed that I could not canvass all this literature in the time at my disposal, and I dropped consideration of James in order to concentrate on Weber.

During that semester there was very little opportunity for any leisurely engagement in nonacademic activities. I did accompany Prof. Stange to Bursfelde in late October and again in early January, and Hilda and I spent a weekend in Kassel in mid-December; but we could usually be found working on our respective assignments. Hilda maintained the apartment with the help of the maid, did the daily shopping on foot, conducted the necessary correspondence, kept me and my clothing in repair, and found time for reading and reflection. Our absences from each other were infrequent and never of long duration. I attended morning classes with some regularity and would read in the library between sessions; but I preferred to work at home, and it was at my desk there that I spent most of my time. However, one exercise in learning kept me from home one evening a week: a number of us students had formed an “Aristotle Club,” and at our weekly meetings we studied the Greek text of Aristotle’s Physics. Out of courtesy to a foreigner, my companions made me chairman of the group, but the pressure of work forced me to leave the club when the first semester came to a close.

We were, of course, not always working. Our accustomed regimen tended to be relieved by a perusal of the daily newspaper, an occasional trip to the movies, visits on selected evenings to the Rathskeller to drink a stein or two of beer and listen to German folk-songs, attendance at church on Sunday mornings, and walks through the neighborhood or on the wall on Sunday afternoons. Nor were we without visitors, and conversations with the Stanges occasionally took place. But there was little room for fun and games.

At the end of the first semester, in mid-March, I had gone through almost all of Weber’s writings, had assembled copious notes, and was ready to do my own writing; but there was still school to attend. During the second semester I took eight hours of course work: Prof. Heyse’s seminar on “Ubingen in die Grundfrage der Wissenschaft,” in which we touched on a variety of issues in science and philosophy, and his class on “Der jetszege Lage Europas,” in which he praised the attempt of the Nazis to transform European culture along Aryan lines. I also heard lectures on Nietzsche by Prof. Baumgarten and on German Idealism by Prof. Hirsch. But I put most of my energy into a mastery of Weber’s thought and into a scrutiny of the empirico-rational method he employed. During April, May, and the first two weeks of June, I labored on my dissertation, with little time for sleep or recreation. Hilda endured my preoccupation with fortitude and patience, though not without lonesomeness and pain. I also suffered under frustrations, ineptitudes, and exhaustion; but I finished writing in early June and had a typewritten copy of my dissertation in the hands of the faculty on June 15. It was written entirely in German and bore the title: “Eine Untersuchung zu Max Weber’s Religionssoziologie.”

At the end of the first semester, in mid-March, I had gone through almost all of Weber’s writings, had assembled copious notes, and was ready to do my own writing; but there was still school to attend. During the second semester I took eight hours of course work: Prof. Heyse’s seminar on “Ubingen in die Grundfrage der Wissenschaft,” in which we touched on a variety of issues in science and philosophy, and his class on “Der jetszege Lage Europas,” in which he praised the attempt of the Nazis to transform European culture along Aryan lines. I also heard lectures on Nietzsche by Prof. Baumgarten and on German Idealism by Prof. Hirsch. But I put most of my energy into a mastery of Weber’s thought and into a scrutiny of the empirico-rational method he employed. During April, May, and the first two weeks of June, I labored on my dissertation, with little time for sleep or recreation. Hilda endured my preoccupation with fortitude and patience, though not without lonesomeness and pain. I also suffered under frustrations, ineptitudes, and exhaustion; but I finished writing in early June and had a typewritten copy of my dissertation in the hands of the faculty on June 15. It was written entirely in German and bore the title: “Eine Untersuchung zu Max Weber’s Religionssoziologie.”

It happened that at that very time Hilda’s widowed mother was enroute to The Netherlands for a visit with her brother Harry Veldsma in Appeldoorn. Hilda had agreed to meet her at the port of Rotterdam, and she left for The Netherlands by train on June 16. During her ten-day absence I saw my dissertation through the press: a hundred printed copies flowed from the “Dieterichsche Universitts Buchdruckere,” a number of which were distributed to members of the faculty and the librarian. This private printing was in fulfillment of a university requirement and was done at the students’ expense. Hilda returned to Gottingen on the 27th of June and reported how frightened she had been when she was removed from the train at the German border and interviewed in the station by an officer of the SS. It turned out, however, that she was guilty of nothing but a failure to renew her visa; and after she paid the standard fee, the officer sent her on her way with all her papers in order.

The oral examination (Mndlichen Prfung) that I was required to undergo took place on June 30: from nine to twelve o’clock in the morning and from two to five in the afternoon, four members of the philosophical faculty and two members of the theological faculty questioned me on a whole range of issues in philosophy and theology. I entered the inquisition chambers with some trepidation, but I was soon put at ease, and I sensed at day’s end that the Herr Professors were not displeased with my responses.

The faculty needed time to read and evaluate my dissertation, and in the interval between inspection and judgment Hilda and I made a trip to Berlin. On three mid-July days we explored the city and its environs and were favorably impressed with its sights and sounds. Shortly after we returned from Berlin and Potsdam, some student friends invited me to attend a farewell party. Six or seven of us gathered that evening in someone’s small apartment, where there was food, a fair quantity of beer, and some champagne. We talked a great deal, ate a lot, and lifted glasses in “Brderschaft.” But I failed to notice that the clock was ticking the hours away, with the result that I arrived home in the company of Fritz Gebhardt a few hours after midnight. Needless to say, an anxious and sleepless Hilda had some unflattering things to say when I came into her loving presence.

On July 27, 1938, the university awarded me a doctorate in philosophy with the notation “Sehr Gut.” With my degree in hand, and the diploma safely tucked away, my study at the University of Gottingen came to an end. In the next few days we bade goodbye to our friends and packed our bags, and on July 30 we left the scene of our many adventures. We boarded the train for The Netherlands, where new experiences, some painful to record, awaited us.

The busyness of the last several months had not disposed us to follow world affairs or observe events happening outside our closed circle. But I remember staying up late one night in June to hear on the radio that Joe Louis had bested Max Schmeling, the pride of Germany, in a boxing match that lasted but two minutes. This blow to German pride paled into insignificance, however, when compared to the national jubilation that attended Hitler’s annexation of Austria on March 15, 1938, and his seizure of the “Sudetenland” from Czechoslovakia in May. The significance of these events did not escape our notice, and I remember telling Fritz Gebhardt that, though we were now good friends, it was not unlikely that in the not too distant future we would be locked in mortal combat.

* * * * * *

Among the people in Gottingen with whom I had dealings, there are some whose names and faces I am unable to recall. But there are others whom I have not forgotten, and of whom I can give a fair account even though their identities are wrapped in the mists of fading recollections. Among these are a number of my instructors. I remember Prof. Otto Weber as a large and burly man who delivered animated lectures with an uncommon intensity. A member of the Reformed church, he was a “Barthian” of sorts, although he was not uncritical of the theology of crisis. When I knew him he was engaged in translating Calvin into German, and he later published an introduction to Barth’s theology. I studied Calvin’s doctrine of the church with him and regularly attended his lectures on the foundations of dogmatics. Those early lectures grew into a book, the first volume of which appeared in 1955; a second appeared in 1962, and both volumes were published in English translation by Eerdmans in 1981-83. Born in 1902, Weber was only six years older than I. Although we were relatively close in age and shared a common faith, our temperaments were diverse, and my appreciation of his competence and erudition was not attended by intimacy or fellowship. I sensed, however, that he regretted my move from theology to philosophy.

Prof. Joachim Jeremias was a mild-mannered, soft-spoken, gentle man whose kindliness and charity endeared him to all his students. He was a reputable scholar, versed in all the Mideastern languages and cultures and master of every critical apparatus and technique; yet he interpreted the New Testament along evangelical lines and in accordance with his own deep Christian faith. He was a member of the Lutheran “Bekenntniskirche” and shared in its hostility to the regnant anti-Jewish sentiments of the general populace. I took a number of courses with him and was a guest in his house several times.

I heard Prof. Friedrich Gogarten lecture on ethics. He was not an inspiring lecturer, nor were his presentations always lucid; but they had substance and quality even though they were not exactly to my taste. His “Barthian” contempt for metaphysics, his “Lutheran” contempt for good works, and his rejection of Calvin’s sensus divinitatis did not speak to my condition. Gogarten appeared to be more or less a lone wolf, and there was something of tragedy in his bearing. An early associate of Karl Barth, he defected and joined ranks with the “German Christians,” but I suspect he was too conservative to feel entirely at home with them. A student of Troeltsch, he went through an existentialist phase before meeting up with Barth, but he remained a traditional Lutheran in his ethics of fixed creational ordinances and of the opposition between law and gospel.

Emanuel Hirsch stood to the left of the above colleagues. Formerly a professor of church history, he was at my time a professor of systematics and the dean of the theological faculty. I attended a number of his lectures on the “Geschichte der evangelischen Theologie” and took a course with him on German Idealism, a subject in which he was an acknowledged authority. He was also a close student of Kierkegaard and published works on that seminal thinker. He was a friend of Paul Tillich, and the two shared an affinity for an existentially tinged philosophical idealism. A “liberal” Christian, he had no sympathy for Barth and was an avowed “German Christian” with marked Nazi loyalties. He was withal a most accomplished and erudite scholar who handled facts and concepts with astounding facility, and his brilliant lectures commanded a large following.

Of Hempel in Old Testament and Drries in church history I can say very little. I attended a few of Hempel’s lectures but soon discovered that he evacuated Scripture of all supernatural revelation, and I went elsewhere. But I did, at his suggestion, buy a copy of the Septuagint, for I can still hear him say, “Meine Herren, haben sie eine Septuagenta? Wenn sie keine haben, verkaufen sie alles was sie haben, und kaufe eine.” I took no courses with Drries but had a number of conversations with him and liked him very much. He was a wholesome Christian who publicly espoused the cause of a confessional church loyal to Scripture.

My instructors in philosophy were of a different sort. Prof. Heyse, director of the philosophical seminar, with whom I did most of my work, was a staunch supporter of the Hitler regime and an open apologist for cultural Aryanism. A Kantian of sorts, he was a student of existentialism and was learned in the history of Western thought. Like Rosenberg, he deplored what he regarded as the Semitic-Christian overlay upon European culture. I would not have known this, or known it as clearly, had I not read his book Idee und Existenz, because, except in one course, he kept pretty close to abstract philosophy. In this book, however, he attempted to show how Augustine had clothed Greek thought in Christian garb, how the unholy alliance between Athens and Jerusalem had polluted Occidental thought, and how necessary it was to return to the Greek tragedies in order to give the Teutonic peoples a charter and a future. Of course, I did not buy this thesis, but I found Heyse personally attractive and ingratiating, and he always stood ready to assist me in every way he could.

Prof. Baumgarten was of my generation and a likable fellow, but he too was alienated from the church and indifferent to the faith. His specialty was English philosophy, and his sentiments were Humean. Like his mentor, he was an acute philosopher who tended toward skepticism in metaphysics and reserve in ideology. It was this reserve, perhaps, that moderated his adherence to Nazism. However that may be, in our many conversations he never expressed himself on political issues. He was my consultant and “Referent” as I wrote my dissertation, and I found him ever ready to assist and advise. We were far apart in our view of things, but we conducted our engagements in philosophical discussions in friendly fashion, and he found no fault with my critical assessment of Max Weber.

I took a few courses with Professors Knig and Bollnow but had almost no exchanges with them and did not really come to know them. I can only say that Knig’s lectures on “Space-Time” opened new vistas formerly closed to me.

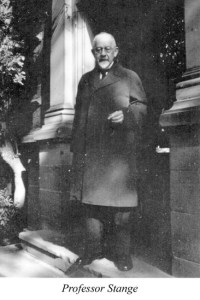

We lived, as I have said, in Prof. Stange’s house, and this brought me into contact with that elderly, bearded gentleman. He had been professor of systematic theology in Gottingen, was now retired, and spent his time translating Italian poetry into German. Author of a textbook on dogmatics, of a volume on Luther’s theology, of another on Kant’s ethics, and of still another on Christian and philosophical worldviews, he enjoyed a considerable reputation in Germany but seems not to have been widely known elsewhere. Hilda and I were not on intimate terms with the family, but we often met one another on the stairs, and we were once invited to a formal dinner in the family dining room, where we met other guests from the academic community. I would sometimes visit Prof. Stange in his study to seek an answer to some question I had, and he always received me cordially; but I was not encouraged to prolong my visit, and from this I learned to practice prudence and restraint. I observed that the maid brought him a bottle of beer just before he retired for the night, and on a few occasions I was present when this occurred; but I was never proffered a libation, on the ground, no doubt, that young men needed no soporific agent to induce sleep. On rare occasions, Stange preached in Bursfelde, but he otherwise never went to church. I once inquired about this, and he replied that he had taught the local preachers all they knew about theology and considered it unnecessary to hear his own material regurgitated on Sunday mornings. I suggested that sermons were proclamations rather than inquiries and that worship was quite unlike an academic pursuit, but he was not overly attentive, and there the matter rested.

We lived, as I have said, in Prof. Stange’s house, and this brought me into contact with that elderly, bearded gentleman. He had been professor of systematic theology in Gottingen, was now retired, and spent his time translating Italian poetry into German. Author of a textbook on dogmatics, of a volume on Luther’s theology, of another on Kant’s ethics, and of still another on Christian and philosophical worldviews, he enjoyed a considerable reputation in Germany but seems not to have been widely known elsewhere. Hilda and I were not on intimate terms with the family, but we often met one another on the stairs, and we were once invited to a formal dinner in the family dining room, where we met other guests from the academic community. I would sometimes visit Prof. Stange in his study to seek an answer to some question I had, and he always received me cordially; but I was not encouraged to prolong my visit, and from this I learned to practice prudence and restraint. I observed that the maid brought him a bottle of beer just before he retired for the night, and on a few occasions I was present when this occurred; but I was never proffered a libation, on the ground, no doubt, that young men needed no soporific agent to induce sleep. On rare occasions, Stange preached in Bursfelde, but he otherwise never went to church. I once inquired about this, and he replied that he had taught the local preachers all they knew about theology and considered it unnecessary to hear his own material regurgitated on Sunday mornings. I suggested that sermons were proclamations rather than inquiries and that worship was quite unlike an academic pursuit, but he was not overly attentive, and there the matter rested.

We did not establish many personal friendships during our stay in Germany, but there were a few persons to whom we were bound by relatively close ties. Chief among these was Wilhelm Vauth. We first met in Hartford, we lived together in Rusbend and Vehlen, and we remained in close touch with each other until the war clouds gathered overhead. Wilhelm was a dedicated Christian who served the Lord with competence and devotion. He was also an incisive thinker whose grasp on things was sure but whose humble spirit and lively sense of humor kept him from falling into theological assertiveness and ideological partisanship. Hilda and I thoroughly enjoyed his company and often profited from his counsel. But the war separated us from each other. It was not merely that we were on opposite sides in the conflict; that could not have destroyed our friendship. It was Wilhelm’s premature death that broke the bond between us. Subject to the draft in spite of his ministerial status, he was inducted into the German army early on and sent to do battle on the Russian front. It was there that he was felled by enemy bullets in August 1941 and sent to a military hospital. It is one of life’s tragedies that this good man died on July 21, 1942, from the effects of the massive wounds he suffered in defense of a cause he loathed.

Less close to us were two other friends, one a young campus minister and the other a budding theologian. Adolf Wischman was the Lutheran “Studentenpfarrer” on the university campus, and we often conferred together about things ecclesiastical and theological. It was he who, upon my request, allowed us to partake of communion in the Lutheran church even though this ran counter to established rules. Adolf survived the war and later became president of the “Aussenamt der evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland.” Hans Kropatchek was a fellow student at the university, and his wife became a close friend of Hilda’s. Hans, whose company I always enjoyed, was studying theology at the time and earned a degree in 1943 on the submission of a dissertation entitled “Das Problem theologischen Anthropologie.”

A person with whom we associated closely throughout the second year of our stay, and who proved to be a faithful friend, was Fritz Gebhardt. He had completed his studies in philosophy, but had not yet written a dissertation, and was currently employed as a functionary in the “Philosophische Seminar.” He was an almost constant visitor at our house, and he and Hilda got along splendidly. Unfortunately, he was not a practicing Christian and did not go to church; but he was a kind, thoughtful, and most pleasant companion. We first met in the “Aristotle Club,” and afterward we did many things together. We even got him to attend church with us on one or two occasions. He ate a fair amount of our food, and when we left Gottingen Hilda gave him all of our dishes and kitchen ware, which he presumably put to good use in his bachelor apartment. While I was riveted to my desk, he would often entertain Hilda with stories or read to her from our copy of Grimm’s “Mrchen,” and when he met Hilda on the street during one of her shopping trips he would invariably invite her to join him for coffee in the nearest coffee house. When I was writing the last chapter of my dissertation, and when the deadline for its submission was drawing near, he stood ready every morning to bring my penciled manuscript to the typist for transcription; for two weeks on end he and his trusty bike stood at attention to perform this most helpful act. For this and other services I owed him a great deal, and in my published dissertation I included his name among those to whom I expressed my heartfelt thanks.

* * * * * *

Were we to depend solely on what we saw with our eyes and heard with our ears, there would not be much to tell about Hitler’s Germany of the middle thirties, for our direct experience of German life was limited by time, and our observations were curtailed and overshadowed by our academic pursuits. What we did notice were various surface phenomena. We saw soldiers parading in the streets, and we once participated in an air-raid drill. The swastika was displayed everywhere, and when we were addressed in the shops or on the streets it was never with a “guten Tag” or an “Aufwiedersehen,” but always with a “Heil Hitler,” accompanied by a stiff-armed salute. Hitler himself was often to be heard over the airways, and what he invariably counseled was strength, pride, determination, and fortitude. Brown-shirted members of the SA and black-uniformed officers of the SS were everywhere, and it seemed that every boy of a certain age was enrolled in some cadre of the “Hitler Jugend.”

Were we to depend solely on what we saw with our eyes and heard with our ears, there would not be much to tell about Hitler’s Germany of the middle thirties, for our direct experience of German life was limited by time, and our observations were curtailed and overshadowed by our academic pursuits. What we did notice were various surface phenomena. We saw soldiers parading in the streets, and we once participated in an air-raid drill. The swastika was displayed everywhere, and when we were addressed in the shops or on the streets it was never with a “guten Tag” or an “Aufwiedersehen,” but always with a “Heil Hitler,” accompanied by a stiff-armed salute. Hitler himself was often to be heard over the airways, and what he invariably counseled was strength, pride, determination, and fortitude. Brown-shirted members of the SA and black-uniformed officers of the SS were everywhere, and it seemed that every boy of a certain age was enrolled in some cadre of the “Hitler Jugend.”

We knew about the Jewish question, particularly as it affected church policies; but no anti-Semitic sentiments were uttered in our presence, and we neither witnessed nor heard about any arrest, imprisonment, or deportation of a Jew. We once saw a sign on a public bathing house that read “Fr Juden zutritt verboten,” but we gave it no special heed since similar signs were well known to blacks living in our own southern states. When we lived on Obere Masch Strasse, the Jewish tobacconist whom I patronized did business without apparent molestation; but when we returned from our summer stay in Vehlen we noticed that his shop was closed. Whether the closing was due to lack of patronage or to sinister action by government agents we could not determine. We did not discuss with our German friends and acquaintances the various occurrences around us, for we were prohibited by the terms of the Fellowship to involve ourselves in politics. Furthermore, the natives were either Nazi sympathizers who were disinclined to share their secrets with strangers or critics who, for fear of reprisals, were careful to keep their sentiments to themselves.

Had it not been for the literature available to me, I should not have known what was really afoot in Germany. Heyse’s volume Idee und Existenz was an eye-opener, and it led me to pick up Hitler’s Mein Kampf and to go from there to readings in Moeller Vanden Bruck’s Das Dritte Reich and Alfred Rosenberg’s Der Mythus des 20 Jahrhunderts. From these and other writings it became evident that the National Socialist movement envisioned not merely the resurgence of a dishonored, bankrupt, and divided people, but nothing less than the transformation of Western culture. Hitler’s proximate goal was to restore to the German people a place in the sun. To this end he repudiated the Versailles treaty, occupied the Rhineland, mobilized the industrial complex in the interest of arms production, built up the army, navy, and air force, and by personal charisma and strong-arm tactics enlisted the real or feigned loyalty of the people to a one-party system and to a “Fhrer” endowed with unlimited powers. Hitler’s intermediate goal was to consolidate the Teutonic peoples and provide them with “Lebensraum,” which is why he seized the Sudetenland and forced the annexation of Austria.