COLLEGE DAYS

(1928-1932)

I entered Calvin College as a freshman in September 1928, and was promptly enrolled in the pre-seminary course. The nine-acre college campus was located in southeast Grand Rapids and was bounded by Franklin Street on the south, by Giddings on the east, by Thomas on the north, and by Benjamin on the west. The campus grounds had been bought in 1909 for $12,000, and the first building erected on it, the so-called administration-classroom building, was dedicated on September 4, 1917. This building stood near the center of the small campus, and the life of the college community was focused on it. It was a large red-brick building adorned at its main entrance with several tall Grecian pillars; it was topped by a cupola that was visible for miles around and served to give the campus its identity. Its main floor contained a chapel with 700 seats, a faculty room, the office of the President, an adjoining space in which the registrar, the treasurer, and a clerk-typist held sway, and several classrooms. The upper floor contained more classrooms and also afforded entrance into the chapel balcony. The locker-laced basement contained rest rooms, a boy’s lounge, a girl’s lounge, and two small laboratories, one for chemistry and the other for the organic sciences. All in all, it very adequately met the needs of the college community.

A second building, a men’s dormitory able to accommodate eighty students and containing in its basement a small, sparsely furnished gymnasium, arose on the corner of Giddings and Thomas in 1924 (a large portion of the money needed to erect it was contributed by Mr. Van Achthoven of Cincinnati, Ohio). On May 8, 1928, a mere four months before I appeared on the scene, the Hekman Memorial Library had been dedicated, and this attractive building graced a corner of the campus at Franklin Street and Giddings. Its books had formerly been housed in a basement room in the classroom building. It was in and around these three buildings that student life revolved during my first years at college. There was no hint in those days of snack bars, playing fields, theaters, music rooms, swimming pools, and other such extravanganza.

A second building, a men’s dormitory able to accommodate eighty students and containing in its basement a small, sparsely furnished gymnasium, arose on the corner of Giddings and Thomas in 1924 (a large portion of the money needed to erect it was contributed by Mr. Van Achthoven of Cincinnati, Ohio). On May 8, 1928, a mere four months before I appeared on the scene, the Hekman Memorial Library had been dedicated, and this attractive building graced a corner of the campus at Franklin Street and Giddings. Its books had formerly been housed in a basement room in the classroom building. It was in and around these three buildings that student life revolved during my first years at college. There was no hint in those days of snack bars, playing fields, theaters, music rooms, swimming pools, and other such extravanganza.

The college traces its lineage back to 1876, but this dating is misleading. What was established in 1876 was a theological seminary charged with preparing ministers for service in the Christian Reformed Church. At the seminary’s beginning there was only one teacher, the Reverend G. E. Boer, and he taught everything from grammar to eschatology. The staff gradually increased, and, in order adequately to prepare the students for ministry, the teachers, besides giving instruction in theology, provided courses in history, philosophy, languages, and literature. The course of instruction embracing those subjects eventually came to be known as the seminary’s literary department; but it was not until 1894, when two laymen, A. J. Rooks and Klaas Schoolland, were appointed to the staff, that nonseminary students were permitted to take classes in this department. Ten years later, in 1904, the seminary’s literary department was so far divorced from the seminary as to be called the “John Calvin Junior College,” and it could be argued that it was in this year that Calvin College really came into existence. The two-year junior college added a third year in 1910, but it was not until 1920 that it became a full-fledged four-year, degree-granting college. It awarded its first baccalaureate degrees to eight students in 1921, seven years before I entered its halls.

Rev. J. J. Hiemenga was the first president of the school (serving from 1919 to 1925), and he was succeeded by Professor Johannes Broene (1925 to 1930). The latter amiable gentleman was in charge of the college when I entered it. In 1928 sixteen professors constituted the all-male faculty; in general, each of these teachers was the sole instructor in the subject he professed. Ralph Stob taught Greek; Albertus Rooks taught Latin and served as academic dean; Albert Broene taught French and German; Henry Van Andel taught Dutch and art; Jacob Vanden Bosch taught English; Harry Dekker taught chemistry and served as registrar; John Van Haitsma taught organic science; Edwin Monsma taught physics and assisted in biology; James Nieuwdorp taught mathematics; Peter Hoekstra taught history; Harry Jellema taught philosophy and psychology; Henry Ryskamp taught sociology and economics; Henry Meeter taught Bible and Calvinism; Seymour Swets taught speech and music; and Henry Van Zyl and Lambert Flokstra engaged jointly in teacher training. Two women served in an auxiliary capacity: Johanna Timmer was the librarian and “advisor to the girls”; and Elizabeth Vertregt, a recent graduate, assisted in the library. This was the staff. The salary scale adopted by the board in May of 1928 stipulated that instructors were to be paid from $2,000 to $2,400 a year, associate professors were paid a little more, and the salary of a full professor ranged from $2,600 to $3,300. The president’s salary was set at $4,000. This salary scale was established, it should be noted, when the business boom of the 1920s was in full swing and postwar prosperity was at its peak.

Rev. J. J. Hiemenga was the first president of the school (serving from 1919 to 1925), and he was succeeded by Professor Johannes Broene (1925 to 1930). The latter amiable gentleman was in charge of the college when I entered it. In 1928 sixteen professors constituted the all-male faculty; in general, each of these teachers was the sole instructor in the subject he professed. Ralph Stob taught Greek; Albertus Rooks taught Latin and served as academic dean; Albert Broene taught French and German; Henry Van Andel taught Dutch and art; Jacob Vanden Bosch taught English; Harry Dekker taught chemistry and served as registrar; John Van Haitsma taught organic science; Edwin Monsma taught physics and assisted in biology; James Nieuwdorp taught mathematics; Peter Hoekstra taught history; Harry Jellema taught philosophy and psychology; Henry Ryskamp taught sociology and economics; Henry Meeter taught Bible and Calvinism; Seymour Swets taught speech and music; and Henry Van Zyl and Lambert Flokstra engaged jointly in teacher training. Two women served in an auxiliary capacity: Johanna Timmer was the librarian and “advisor to the girls”; and Elizabeth Vertregt, a recent graduate, assisted in the library. This was the staff. The salary scale adopted by the board in May of 1928 stipulated that instructors were to be paid from $2,000 to $2,400 a year, associate professors were paid a little more, and the salary of a full professor ranged from $2,600 to $3,300. The president’s salary was set at $4,000. This salary scale was established, it should be noted, when the business boom of the 1920s was in full swing and postwar prosperity was at its peak.

Being a denominational college, Calvin attracted students from every sector of the nationwide church. On its campus one could meet young men and women from Washington and California, from the plains states and the Midwest, from Massachusetts and New Jersey, and from several points in between. This rich and enriching amalgam made Calvin a most desirable place to be, and I found it exciting to be in contact with persons of common faith who nevertheless represented diverse cultures and followed differing social customs. What enriched the mixture, too, was the presence on campus of the theological students. The seminary did not yet have its own building. Its classes were held in the administration building on weekday afternoons, and one frequently met seminarians on the grounds. In addition, a goodly number of them lived in the dorm and associated there with members of every college class. This mingling of theological and liberal arts students cemented the bridge between college and seminary and considerably enhanced the quality of life on campus.

I was one of the 89 freshmen who joined the student body in September 1928, and the coming of our class brought the number of registered students to 325. In a school of this size it was easy to become known and to learn to know others, and I felt immediately at home in my new environment. Present were several members of my high school class, as well as a number of people from the Holland and Grand Rapids schools whom I had come to know through our debating and basketball encounters. Then, of course, there were old friends like George Stob, Peter De Vries, John Vander Meer, and others who had come to the college from Chicago earlier.

During my first year at school I did not live on campus. My brother Mart had earlier made friends with Bill Pastoor, who had come to Chicago from Grand Rapids in order to gain additional experience in the butcher trade. Bill visited us often in Chicago, and sometime during the summer of 1928 it was arranged that I should take up residence in the fall with his parents. Upon my arrival in Grand Rapids, I accordingly became a full-fledged boarder in the Pastoor household and a veritable member of the family. Mr. and Mrs. Harm Pastoor lived at 911 Prince Street, within easy walking distance of the college. Living at home besides myself was a son, Don, and two daughters, Edith and Hildred. These children of the house were near my own age, and I very much enjoyed their presence and companionship. Of more than passing interest is the fact that Hildred, the younger of the girls, soon became engaged to my nephew, John Stob, my brother Bill’s oldest child, and the two were eventually married. Mr. Pastoor owned and operated a butcher shop at Leonard and Pine streets on the city’s west side, and during that first academic year I worked every Saturday in his shop defeathering and disemboweling chickens, making hamburger, and, somewhat later, carving out and selling cuts of beef and pork.

The Pastoors were followers of Herman Hoeksema and members of the Protestant Reformed Church, and I did not join them at worship on Sundays. I joined the nearby Neland Avenue Christian Reformed Church and soon became active in its adult Sunday School class. Rev. D. H. Kromminga had until that point been pastor of the Neland Avenue Church, but in June of 1928 he had been appointed to succeed the ousted B. K. Kuiper as professor of historical theology at the seminary, and soon thereafter he vacated his pulpit. Rev. H. J. Kuiper, who had been appointed editor of The Banner that same June, assumed the Neland Avenue pastorate some months later.

Because the pre-seminary course was prescribed and rigid, I experienced no difficulty with registration: there were no options to baffle or confuse a registrant. During the academic year 1928-29, I took eight hours of Greek with Prof. Stob, my second cousin; six hours of Latin with Prof. Rooks; eight hours of Dutch with Prof. Van Andel; six hours of English composition with Prof. Vanden Bosch; and three hours of logic and three hours of psychology with Professor Jellema. My performance in Latin was poor, but I received creditable grades in other subjects, and I was greatly attracted to philosophy. I found Jellema to be a fascinating teacher and his course in logic a delight; I was to be in every one of his classes thereafter and major in his field. But I should also pay tribute to Prof. Vanden Bosch: in his course in composition he made us submit for evaluation one piece of writing every week, and these exercises in literary creation did much to hone our communication skills. Classes were held only in the mornings, many of them beginning at 7:30. That left us with generally unencumbered afternoons and evenings, and in my first year I was able to devote much of this free time to my various studies.

I made a number of new friends that year, perhaps the closest bonds being with two fellow preseminarians, Rod Youngs and Ed Borst. We would sometimes study together, but more often we simply met for small talk spiced at times by serious discussion of certain controversial subjects. The social life of the school also brought me into contact with the female students, but I formed no steady attachment to any of them.

The whirl of things involved me in a number of extracurricular activities. I naturally participated with the whole student body in the “Soup Bowl,” an afternoon of fun and games and an evening of banqueting that inaugurated the school year and was designed to foster student fellowship. It seems that it was customary for the freshmen to repay the sophomores for their staging of the Soup Bowl by giving them a party. For some unknown reason I was asked to organize and chair the party, and since the party was judged to be a success, I came quite accidentally into the good graces of many of my classmates.

Some of us who were pursuing the preseminary course believed we should do something to master the Dutch language, so we decided to establish what came to be known as the Freshmen Dutch Club. At our rather irregular meetings we tried to help one another unravel the intricacies of Dutch grammar and to traverse safely the labyrinthine ways of its arbitrary genders. Prof. Van Andel was the faculty sponsor of this fourteen-member club, and at its first meeting I was elected president of the group.

There existed on campus a much larger Knickerbocker Club, also sponsored by Prof. Van Andel and designed to perpetuate the Dutch tradition on campus and to preserve its heritage. It turned out that year to be a sort of drama club, for its main activity was to stage a lengthy play called The Siege of Leyden, in which I played as one of a small number of alderman.

Judging that I could not spare the time for basketball, I made no effort to make the junior varsity team, but I did go out for debating. In the intraschool contests held to assist Prof. Vanden Bosch in selecting members of the varsity inter-collegiate team, George Stob, Peter De Vries, and I argued on the affirmative side of the proposition “Resolved that our jury system be abolished.” We met a team that had previously eliminated another. On January 24, 1929, we debated William Frankena, Vernon Roelofs, and Jack Westra, and in the opinion of the Chimes reporter we bested the opposition; but the faculty judges ruled against us and we meekly accepted their verdict. George Stob and Peter De Vries were subsequently made members of the varsity team, and I was made a member of the freshman team. On March 18, 1929, Peter Eldersveld, Henry Dobbin, and I debated a veteran Ferris Institute team that had already scored eleven victories, and we went down by a score of 0-3.

The student body was normally a law-abiding group, but in November 1928 it went on a rampage. Word had been received that Herbert Hoover had defeated Al Smith for the presidency of the United States, and on the next day the students declared a holiday. President Broene urged students to return to classes, but most refused, and a few of the leaders, mostly seniors, were subsequently roundly censured.

Grand Rapids was a picture in the first fall of my residence there. Its tree-lined streets contrasted markedly with the shadeless pavements of Chicago, and I remember vividly the sensations of sound and smell that accompanied my walking on the leaf-strewn sidewalks of the city. These sensations prompted me to write in November 1928 a tribute to

A Leaf

I could not help noticing it. It fluttered down beside me, grazing my cheek in its precipitous descent, and fell prostrate at my feet. The wind had done it, had dethroned a king, had shattered a masterpiece. As I watched, it made convulsive starts in haughty protest to its deposition. Through its contortions its delicate outline only whispered the excellence of its former architecture. The tender nourishing fibers, retaining a suggestion of their original green, were imbedded in a field of gold that deepened toward the edges into a blush. The harmonious blend of tints was a symphony. A gust of wind swept it into the gutter.

During the course of that year I wrote my parents regularly and returned to Englewood as often as I could. I spent Thanksgiving Day and the Christmas holiday at home, but I would thereafter not go back to the home on May Street, for in the spring of 1929 my parents moved into a house built for them at 1330 South 57th Street in Cicero. It is there that I lived during the summer of 1929, and it was from here that I traveled each day to my desk at Thomas S. Smith’s produce house, where I continued to be employed.

* * * * * *

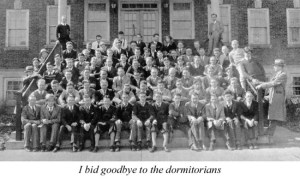

I began my second year of college in September 1929. Having earlier informed the Pastoors that I would be living on campus that year, I found myself at the start of school sharing a dormitory room with Arthur Kapteyn, a classmate whom I had not previously known but with whom I enjoyed a pleasant association as long as we lived together. We each paid six dollars a week for our room and board. The room we occupied was suitably furnished, and, with our bunks properly stacked and our desks judiciously placed, there was ample space in which to move around and accommodate guests. The room boasted no wash or toilet facilities; for our ablutions we had to resort to the communal lavatories located at the end of the hall. Three meals a day were served cafeteria-style in the basement dining room, and, although some complained at the repetitious fare, we ate, I judge, as well as most of us would have at home, and the company at table was not a thing to be despised. Security regulations were nonexistent: doors were never locked, and there were no curfews; we were free to come and go as we pleased.

I began my second year of college in September 1929. Having earlier informed the Pastoors that I would be living on campus that year, I found myself at the start of school sharing a dormitory room with Arthur Kapteyn, a classmate whom I had not previously known but with whom I enjoyed a pleasant association as long as we lived together. We each paid six dollars a week for our room and board. The room we occupied was suitably furnished, and, with our bunks properly stacked and our desks judiciously placed, there was ample space in which to move around and accommodate guests. The room boasted no wash or toilet facilities; for our ablutions we had to resort to the communal lavatories located at the end of the hall. Three meals a day were served cafeteria-style in the basement dining room, and, although some complained at the repetitious fare, we ate, I judge, as well as most of us would have at home, and the company at table was not a thing to be despised. Security regulations were nonexistent: doors were never locked, and there were no curfews; we were free to come and go as we pleased.

The dorm was under the jurisdiction of a faculty committee on housing, but its internal affairs were governed by student officers appointed by that committee. During that year, Frank De Jong, a senior seminarian, functioned as president: he was charged with preserving order, with licensing in-house programs, and with maintaining good relations with the students, the resident matron, and the kitchen staff. He was also obliged to keep in touch with the faculty supervisors and report to them any misdemeanor thought worthy of corrective discipline. As befitted his office, he lived alone in a private room which, being unattended in his absence, was on occasion roughed up by pranksters. Yet he was a friendly fellow and well-liked, and he served us admirably.

There was, I believe, a washing machine in the basement of the dorm, but it was not much used. I followed the example of many and sent my laundry home by parcel post in a sturdy cardboard box suited for the purpose. The box of clean clothes that my mother returned was invariably stuffed with fruit and cookies and sometimes with a bit of money or a new item of apparel. And, of course, it always contained a reassuring and admonitory letter. The dorm also boasted a barber shop of sorts: senior student Gerrit Vander Ziel occupied a private ground-floor room just off the lounge that was equipped with a barber’s chair, and it was he who cut our hair for a nominal fee while discoursing learnedly on topics philosophical. We had similar interests, and I found my visits to his shop both diverting and instructive.

It is fair to say that a generally Christian atmosphere prevailed in the dorm. All of us had been brought up in the church, we had come to this school because of its Christian stance and witness, and most of us were preparing for Christian service in one field or another. Our life together largely reflected these facts. Meal times were accompanied by devotions; and we were expected to attend church on Sundays as well as participate in the morning chapel services held daily in the college auditorium, and this we normally did. Dancing and card-playing were forbidden, and the rules against these things were generally observed: I know of nobody who visited ballrooms, and except for an occasional game of rook, few of us spent our time at cards. Movie attendance was banned, but this proscription met with little favor and was widely ignored. In the tradition of the Dutch, almost everybody smoked, and some of us did not disdain an alcoholic drink. We were not allowed, of course, to bring beer or liquor into the dorm, and in any case the national prohibition law was still in effect; but there were “speakeasies” in Grand Rapids, and the purchase of a pint of smuggled gin occasionally occurred. But the practice was not widespread or in any given case habitual.

In other respects, we residents of the dorm behaved, I suppose, as students so domiciled have always behaved. We burst into each other’s rooms without notice and at inconvenient times. We engaged in idle banter. We hazed pretentious freshmen. We knotted the bed sheets of disfavored persons or, for their dousing, balanced a bucket of water atop their doors. We simulated warfare by exploding firecrackers at midnight. We mounted an occasional raid on the unguarded kitchen pantry, and we often slept too little. But it was not all horseplay. We studied, too, and in small groups we often engaged in serious discussions of important matters. And we formed lasting friendships.

I was fortunate that year to come into close association with Henry Zylstra and John Hamersma, to whom I remained firmly and affectionately bound until in later years their untimely deaths wrenched them from my side. The three of us formed with others a small band that came to be know as the “Friggers”: included in the group were Gus Frankena, Leroy Vogel, Don Stuurman, Rod Youngs, and Art Kapteyn. We stood on campus in friendly rivalry with another, somewhat “bohemian,” group known as the “Conblos,” which included among its members George Stob, Peter De Vries, Syd Youngsma, Red Huiner, Peter Lamberts, Ted Jansma, and Herb Brink. Challenged to a basketball game, we once played against the Conblos in rented tails before a large crowd of appreciative spectators. For a while we had a mascot, a garden snake we called Adolph, which reptile made its home in a large jar I kept in my room. But it came to land one day, whether by accident or design, none seemed to know, in the dorm matron’s bathtub, where it was “done in” by Mr. Norden, the school custodian. We were, of course, saddened by Adolph’s demise, and in a November 1929 issue of Chimes, I wrote a fitting epitaph for him.

But we normally engaged in more intellectual pursuits. I was now a sophomore, and at a meeting held early in the year, I was elected president of the class and by virtue of my office made a member of the student council. The council was composed of eight members, two from each class. As a mediator between faculty and students, the council undertook to strengthen intraschool relationships, to foster mutual understanding, and to assist in the reparation of such breaches as might occur in a school where numbers are small and contacts frequent.

The membership of the council underwent a change early in the year, and thereby hangs a tale. George Stob, a senior, had been elected president of the council in September, and Peter De Vries, a junior, had been elected vice president; but they unfortunately did not remain in office long. It seems that Leo Peters, a sophomore at the time, decided to build a “safe” fire on the dorm’s flat roof as a prank and thus provide the populace with a harmless “scare.” He required for his purpose a large sheet of protective asbestos and, of course, the fuel for burning. But having at the time no means of transportation, he enlisted the services of Peter De Vries, who owned a car and who happened to be in the company of George Stob at the time. The three of them set out on their errand, procured the required materials, and brought them back to the campus. Stob and De Vries then left the scene and took no part in the ensuing conflagration. However, Peters and some companions started and manned a roof fire of some proportions which, being seen and reported by fearful neighbors, brought out the fire department and caused considerable excitement. No damage was done, except to the composure of the neighbors and to the sensibilities of the faculty’s discipline committee. What punishment Peters received I do not recall, but George Stob and Peter De Vries were held to be accessories to the “crime” and were deprived of their offices. John Dolfin was thereupon elevated to the presidency, and Henry Zylstra became vice president; I served the council as secretary.

The membership of the council underwent a change early in the year, and thereby hangs a tale. George Stob, a senior, had been elected president of the council in September, and Peter De Vries, a junior, had been elected vice president; but they unfortunately did not remain in office long. It seems that Leo Peters, a sophomore at the time, decided to build a “safe” fire on the dorm’s flat roof as a prank and thus provide the populace with a harmless “scare.” He required for his purpose a large sheet of protective asbestos and, of course, the fuel for burning. But having at the time no means of transportation, he enlisted the services of Peter De Vries, who owned a car and who happened to be in the company of George Stob at the time. The three of them set out on their errand, procured the required materials, and brought them back to the campus. Stob and De Vries then left the scene and took no part in the ensuing conflagration. However, Peters and some companions started and manned a roof fire of some proportions which, being seen and reported by fearful neighbors, brought out the fire department and caused considerable excitement. No damage was done, except to the composure of the neighbors and to the sensibilities of the faculty’s discipline committee. What punishment Peters received I do not recall, but George Stob and Peter De Vries were held to be accessories to the “crime” and were deprived of their offices. John Dolfin was thereupon elevated to the presidency, and Henry Zylstra became vice president; I served the council as secretary.

I also became a member that year of a campus literary club. We called ourselves the Pierians since our purpose was to “drink deeply of the Pierian Springs,” as Alexander Pope advised. We met monthly under John Timmerman’s presidency and Prof. Vanden Bosch’s sponsorship, and at every meeting we discussed the latest Literary Guild and by turns presented a paper on anything from poetry to drama.

I also became a member that year of a campus literary club. We called ourselves the Pierians since our purpose was to “drink deeply of the Pierian Springs,” as Alexander Pope advised. We met monthly under John Timmerman’s presidency and Prof. Vanden Bosch’s sponsorship, and at every meeting we discussed the latest Literary Guild and by turns presented a paper on anything from poetry to drama.

I was elevated that year to a position on one of the two varsity debating teams. The affirmative team consisted of Bill Frankena, Vern Roelofs, and Henry Dobbin; Hank Zylstra, Rod Youngs, and I composed the negative team. The issue we addressed was unilateral disarmament, and our team argued against it. We engaged in three debates: one against Central Michigan College at Mt. Pleasant, one against Michigan State Teachers at home, and one against Hope College in Holland. We were fortunate enough to win all three contests. The highlight of the debating year, however, was marked by the appearance on our campus of a team from Purdue University. Prof. Vanden Bosch, our coach, shuffled his lineup and appointed Bill Frankena, Hank Zylstra, and me to engage the visitors in debate. Dressed in rented tuxedos, we conducted the debate before a large audience in the college auditorium, and three outside judges were unanimous in their judgment that we had won.

Two additional events of some significance shaped the contours of my life that year. Both were connected with trips to Hope College.

One day three of us traveled to Holland for a debate only to find that we had misread the calendar: no debate was scheduled for that day. What then to do? Time was on our hands, and we were reluctant to return immediately to Grand Rapids. Some one of us then espied a movie house on Main Street and suggested that we enter and discover what went on in there. I was now twenty-one years old and had never seen a movie. Indeed, a short time earlier I had ridden to Chicago with a group of students, and when, in the middle of our trip the car broke down and had to be towed to a garage for repairs, I had refused to join my companions when they decided to attend a local movie. I preferred, I had said, to preserve my innocence. So I had sat for four long and solitary hours in a cluttered garage sheltering myself from the contagion of that which I had been taught to consider “worldly.”

But now, with some trepidation and yet with a certain resolve, the three of us Hank Zylstra, Rod Youngs, and myself bought a ticket and went in to see a movie. I don’t remember what it was about and who played in it, but on our trip home we judged that we had been pleasantly entertained and had suffered no ill effects from our fall from grace.

A week or so after this adventure, our scheduled debate with the team from Hope College took place and we emerged the victors. Upon arriving home from Holland, Hank and Rod repaired to their own quarters and I entered the dorm with the news of our victory. A number of my friends thereupon suggested that we celebrate by lighting and tossing a firecracker that some enthusiast had produced. Emboldened by the victory, I consented. I don’t remember whether I held the firecracker, or lit it, or simply threw it; the whole thing was a communal affair and my involvement in it was only partial. But the dorm president heard the loud report, and the next day Don Stuurman and I were summoned to appear before the faculty’s housing committee. Finding us guilty of a serious offense, the committee ordered us to vacate the dorm forthwith. So in March 1930, Don and I moved into a shared room that we rented from a widow lady who lived on Benjamin Avenue near Alexander. The irony of the situation came home to a number of us when, near the end of the school year, the chairman of the faculty’s committee on housing, Prof. Henry Ryskamp, accosted me on campus and informed me that I had been selected to be president of the dorm the following year. When Prof. Ryskamp urged me to accept the appointment, I thanked him for the trust and confidence the committee had placed in me and said that I would gladly undertake the task. So ended the firecracker episode.

There was on campus a chapter of the League of Evangelical Students. This league had been organized in Pittsburgh in the spring of 1925 by Princeton Seminary students who were inspired and sponsored by Professors Machen and Wilson. In the ensuing years, chapters of the league were established at a number of colleges and universities on the east coast and in the midwest. The Calvin chapter embraced very nearly the entire student body, and at a meeting held at year’s end I was asked to head the group and preside at its meetings during the next academic year.

While all these things were going on, college was, of course, in session. Books had to be read, assignments completed, and requirements met. This kept me busy. During that academic year of 1929-30, I took four hours of Reformed Doctrine with Dr. Meeter, six hours of Greek with Prof. Stob, six hours of Latin with Prof. Rooks, six hours of Dutch with Professor Van Andel, six hours of English and American literature with Prof. Vanden Bosch, six hours of philosophy (introduction to philosophy and Greek philosophy) with Dr. Jellema, and four hours of what was called physical education (but which consisted of little more than calisthenics and team play in the gym).

Campus life was not insulated from the outside world, and many of us kept in some touch with what was going on there. We took note of the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day massacre of seven gangsters on Chicago’s North Clark Street by Al Capone’s henchmen. We read in the papers that Richard E. Byrd had flown over the North Pole in a tri-motored plane, and we were told in news reports that Albert Einstein had recently propounded a radical new theory about the space-time universe. Walter Lippmann published A Preface to Morals in 1929, and when it came into my hands during that academic year, I read it with great delight. Of religious interest was the 1929 Lateran Treaty, by which the Vatican was established as a city state and the Pope was recognized as a sovereign prince. So was the September opening of Westminster Theological Seminary, with a teaching staff that included three sons of the Christian Reformed Church Cornelius Van Til, Ned Stonehouse, and R. B. Kuiper.

Momentous, of course, was the Wall Street stock market crash of October 27, 1929. Herbert Hoover had been inaugurated as president in March and, with business booming, he had promised a car in every garage and a chicken in every pot. But things did not turn out that way. By the end of 1929, stockbrokers had lost forty billion dollars in paper value, hosts of speculators went broke, and thousands of little people lost their jobs. The Great Depression that followed the crash was not to reach its depth until 1932, but within three months of the market’s collapse a blight fell over the land. The members of my family did not deal in stocks, and having no wealth to lose they lost no fortunes. But they, like most other people, were to suffer from the Depression through unemployment, lessened income, and in various other ways. We who were students did not stand in the eye of the storm and suffered no real hardships. With our stipends intact, we may have even gained by the radical fall in prices. But as time went on and the Depression deepened, we could not but observe how great and painful was the distress of the general populace.

In the summer of 1930 the Thomas S. Smith establishment still stood firm, and when school let out I was back at my desk at the South Water Market for my fifth summer of employment. I have no vivid memories of how I spent my summer evenings, though I seem to recall that I went out a few times with a young lady from a neighboring church and once with a high school classmate. These liaisons were, of course, casual and I was able to return to school unencumbered by romantic ties.

I lived all summer with my parents and Mart, and most of my married brothers and sisters were near neighbors. This afforded me plenty of good company, and I must have spent a good deal of time with them. I was probably indisposed to undertake great adventures, for work at Smith’s was somewhat exhausting. I led a sedentary existence there, but with the years my responsibilities seemed to increase. I was required to balance all the accounts of which I had been put in charge, and this was not always easy. Shipments sometimes went unrecorded by the receiving clerk; at other times manifests were mislaid or bills lost, and this made it difficult to adjust claims. But things were normally put to rights, and on the whole I enjoyed my work. I rode the 12th Street trolley car to and from work, and in my coming I read The Tribune and in my going The Daily News.

We had an hour for lunch, and I ate my bagged sandwiches on the fire escape out back, together with a green pepper and perhaps a peach or apple that I “borrowed” from downstairs. I usually took a walk along the busy street at noon, wandering often into the adjoining black neighborhood, where I was met on every side by dilapidated dwellings, unemployment, poverty, prostitution, and delinquency. The scene was inherently depressing, but I’m ashamed to say that it did not arouse in me the degree of compassion and concern that it should have. Years later I would plead the cause of the disfranchised and deprived people of the ghetto, but at this time a somewhat calloused and unresponsive conscience tended to contemplate these people more as objects of interest than as divinely entitled human subjects bereft of their dignity and suffering from discrimination and abuse.

* * * * * *

I began my third, or junior, year of college in September 1930. The first thing a student wants to do upon returning to school after a summer’s absence is to secure his lodgings and settle in for the long grind. On this score I experienced no difficulty that fall. Because I had been selected as president of the dorm, a pleasant private room in it had been reserved for me. It was located on the second floor, at the northeast extremity of the building, and from my window I could overlook a fair stretch of Giddings Avenue. The room was smaller than the one I had shared with Art Kapteyn the year before, but there was ample space in which to move around and entertain guests, and it was rent free. It contained the usual furniture, but it boasted in addition a comfortable lounge chair that I used for light reading and frequently for napping.

Dorm life proceeded peacefully during my year’s tenure in office. I fielded the usual complaints against this or that regulation; sometimes I had to express to the kitchen staff the residents’ dissatisfaction with the meals; and on occasion I had to quell a minor disturbance or silence a too vociferous crowd of disputants in one or another room. But nothing occurred to seriously ruffle the surface of our communal existence, and no prankster undertook to disarrange my living quarters or discomfit me in any way. I can recall only one occasion on which I had to confront a student in a semi-disciplinary fashion. A somewhat arrogant and pugnacious individual once insolently challenged my authority when I asked him to moderate his behavior. I am perhaps somewhat competitive, but I don’t believe I tend to be combative. But in this instance I backed my adversary against a wall and warned him that admonitions left unheeded might lead to unpleasant physical consequences, and that in order to keep his facial features unaltered and intact, he would be well advised not to puncture my composure further or tax my patience beyond endurance. Although this young man was quite my size and I cannot accuse myself of bullying him, I am not proud of my behavior in this instance: violence or the threat thereof is unsuited to social intercourse and is not the preferred way to bring about compliance even in other contexts. Yet the procedure did prove effective, and this perhaps goes to show that by the employment of second-rate tactics one can reach desired ends. It may even indicate that from relative evil good may come.

There was a scattering of sophomores living in the dorm, and some of them participated with their fellows in putting freshmen down and impressing on the consciousness of the latter an awareness of their inferior status. Hazing did not take place in the dorm, and its existence elsewhere was consequently not one of my official concerns. But an instance of it came to my attention when a freshman dormitorian from the Iowa midlands fell into Red Huiner’s hands. That freshman was Feike Feikema, an extremely tall and muscular fellow fresh from a farm near Doon, and he could have laid Red and his companions low with one swipe of his strong hands, but he heeded his mother’s admonition and practiced submission. Feikema, who came to be employed as an assistant to the janitor and who in the course of that year could frequently be seen in our halls with broom and mop in hand, later became a distinguished novelist and, as Frederick Manfred, came to join David Cornell De Young (’29) and Peter De Vries (’31) as one of the three brightest literary stars that Calvin has produced. In a delightful piece written for the Calvin Spark in 1985, Feikema tells of his initiation into college. He reports without rancor and with evident nostalgia that he and a few of his classmates were waylaid one evening by stalking sophomores. “We were bound,” he writes, “with ropes, carried to the unfinished attic of the new Seminary building, splashed with red paint on our backs, and tied to uprights. We managed to wiggle loose; then spent several hours in the dorm shower room scraping off the paint.” This sort of thing went on at Calvin in those days, but it was done in fun, and the few victims of this horseplay took things in stride and harbored no resentment.

Although the number of faculty members remained constant at eighteen and the student enrollment figures still hovered slightly below the 400 mark, a number of changes took place at Calvin in 1930: by an act of Synod, the school’s official name was changed to “Calvin College and Seminary”; Miss Timmer functioned no longer as “advisor to the girls” but had become dean of women; and Elizabeth Vertregt was elevated to the rank of chief librarian. But the biggest change took place in the president’s office: Johannes Broene had with great reluctance assumed the college presidency in 1925, and in May of 1930 he asked to be relieved of his official duties and restored to the faculty as a full-time professor of psychology. The Board honored his request and appointed in his place Rev. R. B. Kuiper, who a year before had joined the faculty of Westminster Seminary as professor of systematic theology. Mr. Kuiper took office in September 1930 and was replaced at Westminster by John Murray. Worship services in the college chapel were much improved with the installation of a Wangeren organ during the summer of 1930. This three-manual instrument, which Prof. Van Andel played daily with great gusto, was the gift of Mr. and Mrs. William B. Eerdmans, successful local publishers and ardent friends of the school. The number of campus structures grew to four when there arose at the corner of Franklin Street and Benjamin Avenue a spanking new seminary building. The faculty and students of the theological school had since 1917 been quartered in the central administration building; they were now able to take up residence in their own spacious and well-equipped edifice. A gift of the Hekman brothers John, Henry, and Jelle the building was formally dedicated on October 29, 1930, and for thirty long years it served the seminary well.

Things were happening off campus as well. In the course of that year, William Howard Taft died, General Douglas MacArthur became the Army’s chief of staff, Mahatma Gandhi challenged British rule with civil disobedience, and Hitler’s Nazi party grabbed 107 seats in the German Reichstag. But for me and my family these things faded into the background and seemed of little consequence when word was received that my brother Neal had been in an auto accident and now lay dead in a Chicago hospital. The van Neal had been driving was struck and demolished by a train at a railroad crossing, and Neal died enroute to the hospital of the massive injuries he sustained in the crash. He had survived the war, but now, on November 19, 1930, at age 36, he was taken from us and we deeply mourned his passing. He left a wife and three small children. I, of course, attended the funeral with my stricken parents and did what I could to console my grieving sister-in-law. Services were held in the First Christian Reformed Church of Englewood in the presence of a large crowd of friends and associates. Neal had served the Englewood congregation as deacon and as leader of the men’s society, and he was held in high esteem for this as well as for his personal qualities. His sudden and tragic death affected many, and he was deeply mourned by all who knew him. Our grief, however, was assuaged by our assurance that Neal had gone to be with the Lord whom he had faithfully served in this life and would now eternally enjoy.

I returned to school chastened by the specter of death and addressed myself with renewed seriousness to the pursuit of learning. In the academic year 1930-31, I studied Reformed doctrine and cultural Calvinism in four semester hours with Dr. Meeter, pursued Greek with Dr. Stob for another six hours, took three hours of medieval history and three hours of Dutch art with Prof. Van Andel, began an eight-hour study of German with Prof. Albert Broene, took six hours of modern European history with Dr. Peter Hoekstra, and continued to work in my chosen field by taking three hours of medieval and three hours of modern philosophy with Dr. Jellema. In addition, I took two hours of public speaking with Mr. Seymour Swets.

I did tolerably well in my assigned courses, particularly in Greek, history, and philosophy, but I nearly failed in Calvinism. Dr. Meeter was an estimable person, and he later wrote an excellent book on Calvinism; but there was something in his posture and tone of voice that turned me off, and I regularly skipped his classes. Aware of my absences, he confronted me at year’s end and said, “You should take the exam and get a decent grade, but, if you choose not to, I have no recourse but to give you a D.” I thanked him and said, “I’ll take the D,” and that dark blot on my record still stands for all to see.

My course work combined with my duties at the dorm kept me busy. I therefore attempted to restrict my extracurricular activities as much as possible. If I was not very successful in that endeavor, it was not for lack of trying. I knew from four years of experience that high school and collegiate debating requires a large amount of preparation and consumes a good deal of time. I therefore determined to sever my connection with the varsity debating team. By this action no harm was done to the school’s forensic program, for Prof. Vanden Bosch had a number of excellent debaters at his disposal, and from these he fashioned teams that performed that year with great distinction and remarkable success. Meanwhile, I was free to devote myself more fully to my studies.

My course work combined with my duties at the dorm kept me busy. I therefore attempted to restrict my extracurricular activities as much as possible. If I was not very successful in that endeavor, it was not for lack of trying. I knew from four years of experience that high school and collegiate debating requires a large amount of preparation and consumes a good deal of time. I therefore determined to sever my connection with the varsity debating team. By this action no harm was done to the school’s forensic program, for Prof. Vanden Bosch had a number of excellent debaters at his disposal, and from these he fashioned teams that performed that year with great distinction and remarkable success. Meanwhile, I was free to devote myself more fully to my studies.

The production of the school annual was the responsibility of the junior class, and when it was proposed in an early meeting that I act as editor-in-chief, I demurred. I distinctly remembered the stress I was under to produce the high school annual, and I had no desire or inclination to repeat the experience. I therefore stoutly resisted every attempt to get involved in the collegiate venture. To my great satisfaction, Gus Frankena was chosen to edit the annual. By way of concession I agreed to serve with Mildred Reitsema as literary editor.

I held no class office that year, but because I had held office the previous year, I was by statute given a seat on the student council. Henry Zylstra, now in his senior year, was elected president of the council, and I was chosen to be vice president. The two of us spent a lot of time revising the constitution in an attempt to give the council more authority in regulating student life, but it was not until the following year that an improved document was adopted.

I held no class office that year, but because I had held office the previous year, I was by statute given a seat on the student council. Henry Zylstra, now in his senior year, was elected president of the council, and I was chosen to be vice president. The two of us spent a lot of time revising the constitution in an attempt to give the council more authority in regulating student life, but it was not until the following year that an improved document was adopted.

The student publication, the Calvin College Chimes, underwent a transformation at the beginning of that school year. Established in 1907, the Chimes had up to that time been largely a literary magazine that was published monthly in pamphlet form. Under the aegis of Peter De Vries, its current editor, and with the assent of several on the staff, the format was radically changed: Chimes became a biweekly newspaper.

Editorials and comments were still to be found in it, but the essays, poems, and other literary productions that had earlier graced the publication were conspicuous by their absence. The change did not meet with universal approval, and I myself wondered out loud whether it represented an improvement; but in a plebiscite conducted at year’s end, the student body endorsed the alteration, and Chimes never thereafter reverted to its former self. I became a member of its staff, serving with Mildred Reitsema, John Timmerman, and Henry Zylstra as one of the four associate editors charged with producing periodic editorials. Peter De Vries resigned as editor on December 18, 1930, ostensibly for health reasons, but more probably under pressure from an administration that took no delight in his acerbic wit and his sometimes vitriolic attacks on what he regarded as a comatose and moribund tradition. Leo Peters completed De Vries’s term.

Editorials and comments were still to be found in it, but the essays, poems, and other literary productions that had earlier graced the publication were conspicuous by their absence. The change did not meet with universal approval, and I myself wondered out loud whether it represented an improvement; but in a plebiscite conducted at year’s end, the student body endorsed the alteration, and Chimes never thereafter reverted to its former self. I became a member of its staff, serving with Mildred Reitsema, John Timmerman, and Henry Zylstra as one of the four associate editors charged with producing periodic editorials. Peter De Vries resigned as editor on December 18, 1930, ostensibly for health reasons, but more probably under pressure from an administration that took no delight in his acerbic wit and his sometimes vitriolic attacks on what he regarded as a comatose and moribund tradition. Leo Peters completed De Vries’s term.

The Calvin chapter of the League of Evangelical Students had a membership that year of over two hundred. As president, I was charged with giving the organization some direction, and I was ably assisted by many willing workers. We collected funds through solicitation, did deputation work at neighboring colleges, and on January 23, 1931, held a daylong regional conference featuring prominent religious leaders. The assembled students, representing several colleges and seminaries, were treated that January day to three major addresses by distinguished speakers and were led by knowledgeable persons to consider a variety of subjects relating to Christian witness in five different sectionals. A public meeting held that evening topped off the day and enriched our coffers. The sixth annual national convention of the League of Evangelical Students was held in Philadelphia in February 1931, and I was in attendance as a delegate from the Calvin chapter. For three days, many students from various colleges were led in devotions, speeches, rallies, and discussions by such leaders of the evangelical community as Machen, Craig, Sloan, Glover, Gray, Lenton, Murray, Kuiper, and others. I was privileged to chair the nominating committee, to take lodging in John Murray’s house, and to spend a delightful evening with a few others in the company of J. Gresham Machen. I returned to school enriched by the Philadelphia experience.

The Calvin chapter of the League of Evangelical Students had a membership that year of over two hundred. As president, I was charged with giving the organization some direction, and I was ably assisted by many willing workers. We collected funds through solicitation, did deputation work at neighboring colleges, and on January 23, 1931, held a daylong regional conference featuring prominent religious leaders. The assembled students, representing several colleges and seminaries, were treated that January day to three major addresses by distinguished speakers and were led by knowledgeable persons to consider a variety of subjects relating to Christian witness in five different sectionals. A public meeting held that evening topped off the day and enriched our coffers. The sixth annual national convention of the League of Evangelical Students was held in Philadelphia in February 1931, and I was in attendance as a delegate from the Calvin chapter. For three days, many students from various colleges were led in devotions, speeches, rallies, and discussions by such leaders of the evangelical community as Machen, Craig, Sloan, Glover, Gray, Lenton, Murray, Kuiper, and others. I was privileged to chair the nominating committee, to take lodging in John Murray’s house, and to spend a delightful evening with a few others in the company of J. Gresham Machen. I returned to school enriched by the Philadelphia experience.

I retained my membership in the Knickerbocker and Pierian clubs that year, but I was irregular in attendance at their meetings and did not get deeply involved in their proceedings. I focused instead on two other clubs, one a venerable establishment the Plato Club and the other a quirky new creation with bohemian-like tendencies the Neo Pickwickians. The Plato Club, sponsored by Dr. Jellema, was designed to bring together a small group of people who were interested in philosophy and were ready to prepare discussable papers on a variety of philosophical themes. The club was open to juniors and seniors only, and the number of members was limited to twelve. I joined the club in September. During that year we devoted ourselves to a study of Wallace’s Prolegomena to the Logic of Hegel, a difficult book that taxed our minds but evoked stimulating discussions on a wide range of logical, epistemological, and metaphysical issues. The Neo Pickwickians were a group of friends interested in literature but disposed to pursue belles-lettres in an unconventional way. We incorporated ourselves that year, secured Henry Ryskamp as faculty sponsor, gave ourselves literary names, held our meetings in outlandish places, prepared some serious papers, ate midnight snacks, and had fun. There were fourteen members in the group: of that number, one became an outstanding preacher, two became business executives, one became a lawyer-judge, seven became college and university professors, and one became an editor-publisher.

To top these things off, I entered into a business partnership that year. The furnaces of the day burned coal, and the ashes had to be disposed of somehow. To ease the burden of the householder, John Nieuwdorp and I offered to remove each tub of ashes for the sum of ten cents a tub.

We lined up a fairly large number of customers, including the college itself, bought an old model-T truck, and pursued our trade on Wednesday afternoons and Saturday mornings. I don’t remember how well we fared financially, but I’m sure we didn’t operate at a loss. In any case, we profited physically: lifting large tubs of ashes out of deep basements, tossing the tub’s contents into a truck-bed ringed by high boards, and disposing of the cargo by shovelfuls at the dump must surely have hardened our muscles. At year’s end we abandoned the business and sold our truck to Ed Bierma and John De Bie.

We lined up a fairly large number of customers, including the college itself, bought an old model-T truck, and pursued our trade on Wednesday afternoons and Saturday mornings. I don’t remember how well we fared financially, but I’m sure we didn’t operate at a loss. In any case, we profited physically: lifting large tubs of ashes out of deep basements, tossing the tub’s contents into a truck-bed ringed by high boards, and disposing of the cargo by shovelfuls at the dump must surely have hardened our muscles. At year’s end we abandoned the business and sold our truck to Ed Bierma and John De Bie.

Student life at college, particularly at a co-ed institution, is normally spiced with outings and parties, and I engaged in a fair number of these. In the process I dated a number of girls but formed no attachment to any of them. What I quite vividly remember in this connection, however, is seeing an auburn-haired young lady walking with queenly grace through the library when I was sitting there, and thinking that this was someone I should like to meet some day. It chanced that at year’s end I did meet her under circumstances not particularly auspicious. The girls who made up the KKQ club were holding a farewell party at a beach house near Holland, and I was present as a guest of Ruth G. Sometime during the early evening I tired of the goings-on within and wandered off alone onto the beach and sat down on a bench at water’s edge. To my surprise and considerable delight, two young women who happened to be nearby approached me and began to engage me in conversation. One of them was the girl I had seen in the library. I learned that her name was Hilda De Graaf, that she was a graduate of Grand Rapids Junior College, had subsequently worked as a nurse’s aid at Blodgett Hospital, and had enrolled in Calvin College that year as a junior. Our conversation was short-lived, for I dared not be too long absent from the party. But the meeting was momentous, because five years later this wonderful girl became my dear wife and after fifty-eight years of happy marriage, thank God, she still is.

Before the school year drew to a close, we noted that Prof. Louis Berkhof had been appointed as the first president of Calvin Theological Seminary; that Mr. Harry Wassink had been appointed instructor in physics at the college; that Professors Ralph Stob and Henry Ryskamp had acquired their Ph.D. degrees; and that Miss Vertregt had been married and was being replaced in the library by Miss Josephine Baker. We also noted that, with the Depression deepening and the school’s deficit mounting, the members of the faculty had taken a sizable reduction in their salaries, and that the Christian Labor Association, with headquarters in Grand Rapids, had just been given birth.

In the summer of 1931, I lived with my parents in Cicero and worked for three months in Thomas S. Smith’s wholesale produce market.

* * * * * *

I began my senior year of college in September 1931. In the academic year 1931-32 the college employed nineteen full-time teachers. Fourteen professors formed the core of the staff, and these, with the president, constituted the actual and operative faculty. Three instructors and two assistants stood at their side, but they attended no faculty meetings and took no part in policy formation.

The student body had decreased in size. Enrollment now stood at 355, of which fifty-three were seniors. Gone from the scene were many of my friends: George Stob had graduated as early as 1930; missing since June of 1931 were Peter De Vries, John Hamersma, Jack Lamberts, John Nieuwdorp, Casey Plantinga, Clarence Pott, Bill Spoelhof, Sam Steen, Don Stuurman, and John Timmerman. Most of these had gone off to graduate school in pursuit of advanced degrees Hamersma and Steen in law, Lamberts and Timmerman in English, Plantinga and Stuurman in philosophy, Pott in German, and Nieuwdorp in medicine.

Spoelhof and De Vries traveled other roads: Bill took a teaching job at Kalamazoo Christian High School; Peter returned to Chicago, where, before joining the staff of Poetry magazine, he did odd jobs to keep bread on his table. The absence of these stalwarts diminished me, but there was one consolation: Henry Zylstra was still aboard. Although Hank was of the class of ’31, he had received a one-year appointment at the college as assistant in English and German and as coach of the debating team. This kept him on campus and enabled us to continue our close association and to establish even more securely our already firm friendship.

Spoelhof and De Vries traveled other roads: Bill took a teaching job at Kalamazoo Christian High School; Peter returned to Chicago, where, before joining the staff of Poetry magazine, he did odd jobs to keep bread on his table. The absence of these stalwarts diminished me, but there was one consolation: Henry Zylstra was still aboard. Although Hank was of the class of ’31, he had received a one-year appointment at the college as assistant in English and German and as coach of the debating team. This kept him on campus and enabled us to continue our close association and to establish even more securely our already firm friendship.

After living one year in a family home and two years in the dorm, I was ready for a change of residence.

Before the previous school year had come to a close, my friend Leroy Vogel we called him “Bird” and I had decided to room together in some off-campus apartment. We found a place to our liking at 1213 South Butler Street in southeast Grand Rapids: an aged Dutch lady lived at that address with an unmarried middle-aged daughter, and we discovered that the upper floor of their small house was for rent. After inspecting the premises, we promptly engaged the furnished rooms and moved in a few days before the opening of school. We found the accommodations well suited to our purpose: we had at our disposal a pantried kitchen equipped with stove, pans, and dishes, a good-sized bedroom furnished with twin beds, and a large front room which, after we had brought in our desks, chairs, and bookcases, we were able to convert into a pleasant study area. There was no phone in our apartment, but we were permitted to use the one in the downstairs hall for free when making local calls. Heat and light were furnished, and for our total accommodations we paid twelve dollars a month rent, six dollars apiece.

The Butler Street house stood just south of Hall Street, so we dubbed our place “Butler Hall,” and a hall it soon become, for our friends repeatedly visited us there, making it a meeting place for banter, fellowship, and intramural education. Hank Zylstra was a frequent visitor, and the three of us often engaged in a serious discussion of matters relating to our studies. I remember one evening we were talking about literature. We wondered whether one form of it was better fitted to express the Christian vision than another. We canvassed the merits of the ode, the lyric, the sonnet, the epic, the novel, the drama, and the like, and we had not finished our survey when, looking up, I shouted in amazement, “Hank, there is the sun.” Bird had retired at midnight, but Hank and I, quite unconscious of the passage of time, had been overtaken in our conversation by the dawn.

The Butler Street house stood just south of Hall Street, so we dubbed our place “Butler Hall,” and a hall it soon become, for our friends repeatedly visited us there, making it a meeting place for banter, fellowship, and intramural education. Hank Zylstra was a frequent visitor, and the three of us often engaged in a serious discussion of matters relating to our studies. I remember one evening we were talking about literature. We wondered whether one form of it was better fitted to express the Christian vision than another. We canvassed the merits of the ode, the lyric, the sonnet, the epic, the novel, the drama, and the like, and we had not finished our survey when, looking up, I shouted in amazement, “Hank, there is the sun.” Bird had retired at midnight, but Hank and I, quite unconscious of the passage of time, had been overtaken in our conversation by the dawn.

When two people live together, they must work out a certain division of labor. Bird and I agreed that we would make our own beds and cooperate in the washing and drying of dishes; Bird volunteered to prepare the meals if I would undertake to keep the premises clean. I readily consented to this arrangement, since I possessed no culinary skills but was, on the contrary, an experienced janitor and had mastered the art of dusting and mopping. Moreover, I was loath to see our premises fall victim to Bird’s slovenly household habits. His desk was a mess: piled high with papers, pipes, unwashed sox, apple cores, empty coffee cups, and sundry other items, it resembled a dump, and I sometimes chided him about this sorry state of affairs. I myself am a clean-desk man, and I have often wondered how people of the opposite sort could ever recover an article they sought. But that year I learned that a man with a cluttered desk has hidden powers. Bird, I found, was often able to finger a misplaced paper in the twinkling of an eye, while I, with all my organizational apparatus, was sometimes at a loss to locate a properly filed item that I wished to retrieve.

Bird and I got along famously. We were both seniors, we were both headed for the seminary, we had known each other since freshman days, we were both “Friggers,” and we had a similar outlook on life. We argued, but we never quarreled. When we argued, it was about matters of substance, except when, as in the case of the bread, we argued for argument’s sake and in order to sharpen our wits. Toward the end of a meal Bird would sometimes take a half slice of bread and announce that he could eat no more. “Nonsense,” I said, “if you can eat a half slice you can eat a whole.” Bird attempted a rejoinder but, cutting him short, I added, “Moreover, replacing the half slice destroys the symmetry of the loaf.” This objection seemed not to weigh heavily with him, whereupon I attempted to show that there were physiological, psychological, philosophical, theological, and even economical reasons why his detested practice should be abandoned. He adduced counterarguments but I discredited them all, and this play and interplay continued for months until we tired of it and declared a truce. In later years, amidst running laughter, we fondly recalled our unresolved debate.

I think Bird was a fair cook, but I don’t remember how our eating comported with accepted dietary rules. We purchased most of our food supplies from the Korfker grocery store on the corner of Butler and Hall, and these foods must have served us well, for we maintained both our appetite and our health. Prices were low: I remember buying two pounds of choice pork chops for twenty-five cents, and I know that the ground beef we normally fed on was regularly available at ten cents a pound, or three pounds for a quarter. We did not patronize restaurants, even though as late as 1935 one could visit the Bierstube and dine on pig hocks and sauerkraut, hot German potato salad, a vegetable of the day, and several slices of pumpernickel for $.60, or buy a fried perch dinner for $.35. The cigarettes we sometimes bought were priced at fifteen cents a pack or two packs for a quarter; but we normally contented ourselves with buying a sack of Bull Durham tobacco and a packet of papers and rolling our own. We were, after all, in the midst of the Depression, and we had no money to waste.

We had gone to church regularly in former years, but we tended to “shop around,” and we formed no attachment to any single congregation. In that year, however, we lived within a stone’s throw of the Oakdale Park Christian Reformed Church, and it was here that we regularly attended Sunday services. Rev. Zeeuw was then the pastor of the church, and we enjoyed his preaching. We were saddened, however, when Rev. Zeeuw was found guilty of window-peeping and deprived of his pulpit. What happened to him afterward I do not know; I trust that he found forgiveness and restoration.

It is only fair to report that our studies and bull sessions were interlaced with occasional visits to the movies. There was a theater on Madison Avenue at Hall, and, when an afternoon’s work had exhausted us, we would sometimes seek relief in the dark confines of that establishment. We had to pass through a cemetery to get there and through what is now a hostile neighborhood; but in those days we could walk unafraid and unmolested on the darkest of nights and arrive home unscathed. President Kuiper once saw us entering this church-outlawed establishment, but he evidently made nothing of it, for we were never summoned to his office or in any way reprimanded.

The college was about three quarters of a mile away and we reached it by foot in all kinds of weather. To save time and effort we usually cut diagonally through Franklin Park, though on our way home we sometimes paused to watch the games that were being played there.

Class elections were held at the beginning of the school year, and when the seniors met to cast their ballots, they elected me class president. By virtue of this election, I took a seat on the student council for the third successive year and was appointed council president at the first meeting of that eight-member body. Serving with me were Ann Geerdes, Florence Stuart, Gus Frankena, Enno Wolthuis, Gelmer Van Noord, Carl Kass, and John Daling.

I had something to do with John Daling’s presence on the council. It was believed in the early thirties that freshmen were not in a position to elect class officers, for they were unacquainted with each other and could therefore not make informed choices. The president of the senior class was therefore given the power of appointment, and I exercised that power. After consulting with the dean and the registrar, I named as freshman class president a person whose high school record indicated that he was a man of parts John Daling. Having been named president, he was given his designated seat on the council, and he served it well. John, who was a few years older than I, soon became one of my friends and we later served together on the college faculty. He has since passed out of this life, but I am much indebted to him for many things, in part for his early solicitude concerning our food supply and eating habits. In that year and the one following he expressed his friendship and concern by often coming to Butler Hall bearing fruits and vegetables from his father’s farm and canned meats from his mother’s kitchen.

Through the ratification of a revised constitution, the student council was enabled that year to exercise complete jurisdiction over all school activities and to monitor the activities of the various relatively independent student boards. Numbered among the council’s accomplishments that year was the creation of an official Calvin seal, the inauguration of a new kind of “Soup Bowl,” and the enforcement of an act forbidding the payment of monies for work done on all school student staffs.

I remained a member of the Pierian and Knickerbocker Clubs in 1931-32, but I did not engage much in their activities. My attention was focused rather on the Plato Club. I had joined this philosophical organization at the beginning of the previous year and was happy now to continue my membership in it. At a meeting held in September 1931, twelve of us gathered under Prof. Jellema’s sponsorship to elect the season’s officers. When the ballots were counted, I chanced to emerge as the group’s choice for president, and I continued to chair our meetings throughout the year. The club membership included Enno Wolthuis, Ed Bierma, Elco Oostendorp, Leo Peters, Rein Harkema, Ed Borst, Henry Zylstra, and myself. Prof. Jellema was, of course, our guide and mentor, and under his direction we studied with great profit The Republic of Plato. We met biweekly in various places, mostly in the rooms of the participating members. On November 16, 1931, we met at Butler Hall, and on that occasion I read a paper entitled “What is Goodness?” It was only when the clock struck one that the group disbanded that evening. Our meetings were like that: in smoke-filled rooms, along tortuous paths, with minds stretched out, we pursued the elusive Plato. But, despite our best efforts, we never quite caught up with him.

I remained a member of the Pierian and Knickerbocker Clubs in 1931-32, but I did not engage much in their activities. My attention was focused rather on the Plato Club. I had joined this philosophical organization at the beginning of the previous year and was happy now to continue my membership in it. At a meeting held in September 1931, twelve of us gathered under Prof. Jellema’s sponsorship to elect the season’s officers. When the ballots were counted, I chanced to emerge as the group’s choice for president, and I continued to chair our meetings throughout the year. The club membership included Enno Wolthuis, Ed Bierma, Elco Oostendorp, Leo Peters, Rein Harkema, Ed Borst, Henry Zylstra, and myself. Prof. Jellema was, of course, our guide and mentor, and under his direction we studied with great profit The Republic of Plato. We met biweekly in various places, mostly in the rooms of the participating members. On November 16, 1931, we met at Butler Hall, and on that occasion I read a paper entitled “What is Goodness?” It was only when the clock struck one that the group disbanded that evening. Our meetings were like that: in smoke-filled rooms, along tortuous paths, with minds stretched out, we pursued the elusive Plato. But, despite our best efforts, we never quite caught up with him.

Yet we enjoyed the chase and doubtless were made better by it.

The Calvin College Chimes was ably edited that year by Peter De Visser, a gifted fellow who in later years became book editor at the William B. Eerdmans Publishing House and also the managing editor of the The Reformed Journal. I retained the position on Peter’s staff that I had earlier occupied, and, as one of the three associate editors, I wrote a fair share of the editorials that appeared in print that year.

It was noted in the Chimes and announced in chapel that a J. C. Geenen prize in psychology would be awarded that year to a Calvin student who submitted a winning paper on a topic in that developing field. Challenged by the offer, I prepared over the course of some months a lengthy dissertation on “the Soul” and submitted it to the judges for evaluation. I was pleased to learn at year’s end that my entry had been approved and had been deemed worthy of first prize, a sum of money in an amount I cannot now recall.

When spring came and all nature had burst into life, I was suddenly cast into sorrow by a piece of news from home. A phone call from my brother Tom informed me that Father had been taken seriously ill and was now near death’s door. Responding quickly to the call, I summoned Bird and Hank Zylstra to my side, and these good friends offered at once to drive me home and without delay. When I came into the house, I found my older brothers huddled around the sickbed and ministering as best they could to Father’s needs. His temperature had risen to 105 degrees, but I was able to hold his hand, plant a kiss on his cheek, and express to him my love and deep respect. He squeezed my hand, fastened a kind and reassuring eye on me, and fell into a fitful sleep from which he did not awaken. Father died early the next morning from what the doctor said was lobar pneumonia and pleurisy. The date was April 23, 1932. Father had lived on this earth for sixty-nine years, five months, and twelve days, and now he had been taken up to be forever with his Lord.

I still have a letter that he wrote on April 17, a short week before he died. He was well then, had gone to church twice that day, and wrote how pleasant it was that the minister had preached on one of his favorite texts “My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever” (Ps. 73:26). Mother told me that in the five days that he lay sick he often repeated those words, as well as others so dear to him: “I am always with you; you hold me by my hand. You guide me with your counsel, and afterward you will take me into glory.” That these words were on his dying lips I can well believe, for he lived close to God and served him faithfully all his days.

Father died early on Saturday morning, and the funeral service was held on Tuesday afternoon, April 26, 1932, in the Second Christian Reformed Church of Cicero. The service was conducted jointly by the Reverends P. A. Hoekstra and J. J. Weersing. Interment was in Mount Auburn cemetery, where a small stone slab still marks his grave.

Father died early on Saturday morning, and the funeral service was held on Tuesday afternoon, April 26, 1932, in the Second Christian Reformed Church of Cicero. The service was conducted jointly by the Reverends P. A. Hoekstra and J. J. Weersing. Interment was in Mount Auburn cemetery, where a small stone slab still marks his grave.

When Father died, a part of me died with him. Nearly half a century separated us in age, but no gulf yawned between our spirits, and there was nothing to cut our shared sentiments asunder. We children deeply mourned the passing of our father, but when we laid his body in the grave we took comfort in the fact that his life was Christ and his death gain a sure entrance into the inheritance of the saints. And when the earth closed in upon him, we realized that to keep him in sacred memory we could do no better than to exhibit in our own lives the beauty and godly power of his.